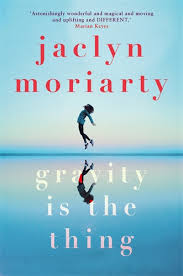

Jaclyn Moriarty is best known for her YA fiction but in her latest adult contemporary fiction novel, the wonderfully light-hearted Gravity is the Thing (Pan MacMillan 2019), she gives us an entertaining and whimsical modern adventure that is written with wit, poignancy and almost – but perhaps not quite – a touch of magic realism. But while, on the surface, this book is a romantic comedy, there is a serious seam running underneath that deals with some big issues of loss, grief, abandonment and mental illness.

Abigail Sorenson is a single mum trying to do it all, including running her Happiness Café, and raising her four-year-old son Oscar (who is completely charming and one of my favourite characters in the book; Moriarty has captured Oscar’s childish imagination, faux serious pronouncements, weird attachment to inanimate objects and inexplicable rules of play with a familiarity that will delight any reader who is a parent). But she is also coping with a terrible loss from years earlier, when her 15-year-old brother – and closest friend – Robert, disappeared on the eve of her 16th birthday. Coincidentally that was also the year that she began to receive in the mail anonymous chapters of The Guidebook, a strange and mysterious self-help book.

The book opens with Abigail receiving an invitation to attend an all-expenses-paid retreat which offers to finally, after 20 years, offer the truth behind The Guidebook and explain what it is really all about. Abigail is convinced that The Guidebook has some unknown connection to her brother’s disappearance, but what she eventually discovers is unexpected. She meets a group of strangers and forms connections that will change her life.

The depiction of Abigail as the over-committed, over-wrought and constantly over-thinking single mum is funny and moving. We are privy to the insight of the stream-of-consciousness thought-processes of Abigail as she deals with family, work and relationship dynamics, trying most of all to be a good mother to Oscar, and to cope with her past trauma. The book is written in an unusual style, with short, sharp chapters progressing the narrative. It comments on the many permutations of the self-help movement or industry. Abigail – and thus, the reader – is asked to believe impossible things; she learns what it means to let go of expectations and preconceived notions, and to explore the open-ended opportunity of magical thinking. The book is peopled with a rich cast of interesting characters and sprinkled with the occasional profound observation: for example, when describing Sydney’s North Shore, she says: ‘There’s diversity here, but it’s concealed behind uniforms. There are broken people here, but they’re pinned together with therapy, Botox, hair dye and designer clothes, rage pegged down with hot stone massage, soothed by high-functioning alcoholism.’ Or this: ‘Maybe, by a certain age, we have all encountered some impossible loss, or at least the accumulation of small sufferings.’ And this, in the Acknowledgements, dedicated to those with missing friends or family members, I found especially moving: ‘The strength required to live with ambiguous loss, with the absence of the one truth that matters the most, is breathtaking.’ Readers of the three Moriarty sisters who are authors – Liane, Nicola and Jaclyn – know what to expect from their books: tender portrayals of family, complex unravelling of relationships, quick-witted examinations of the why and how of our daily lives. For those who enjoyed Minnie Darke’s Star-crossed, and for fans of a rom-com style that is both funny and thought-provoking, Gravity is the Thing will not disappoint.