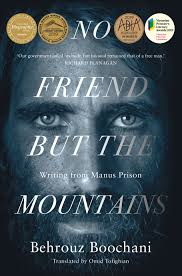

I’ve followed Kurdish-Iranian journalist and advocate Behrouz Boochani ever since he first appeared on Twitter, so it is rather shamefacedly that I admit I have only just read his important book No Friend But the Mountains (Picador 2018). As with so many non-fiction books that explore confronting and deeply distressing issues, this had sat on my bedside table … my head wanting to read it, but my heart knowing that I could never unsee what was inside those pages. And because I have followed his life and career over the past years, especially as his international profile as a refugee advocate has risen, I knew what to expect.

And yet still, I was shocked.

This is a shocking account; each revelation or depiction is more shocking than the last. I read this book with my heart in my mouth, always feeling on the edge of a precipice. Yet it is such a vitally important book for all Australians to read. Boochani’s message needs to be heard by every Australian. It should be required reading on secondary school curriculums. It is terrifying, upsetting and frustrating. It is information that should be made aware to us all, every small detail of fear, every tendril of hope.

Now writing regularly for major media outlets and having won numerous awards for his writing and film-making, Boochani hardly needs an introduction. (If you’ve never heard of him, you definitely need to read this book). Equally important in the journey of this publication is his translator, Omid Tofighian, whose already difficult job was made more so for the fact that this book was written via text messages and WhatsApp, each short entry smuggled out of Manus Island at great risk to Boochani, each entry then carefully translated to retain the beauty and power of his words.

Despite the content, the book IS beautiful. Boochani’s evocative and timeless poetry graces almost every page, poems he wrote while imprisoned, poems he wrote about the lives of other refugees, about his captors, and of his own dreams of release and freedom. The narrative threads between these poems, explaining their source or providing some factual context to their abstract concepts.

The foreword by Richard Flanagan describes the book as ‘prison literature’, ‘a miracle of courage and creative tenacity … despite situations of prolonged duress, torment and suffering’. Flanagan goes on to decry the role of the Australian government in operating offshore detention centres (such as Manus, Nauru and Christmas Island), dehumanising people seeking asylum, incarcerating innocent people like hardened criminals, treating them with disdain and without even the basic necessities of human rights, referring to them each as a number and not by name … with all of these circumstances leading to beatings, torture, rape, cruelty, and self-harm and suicide by those imprisoned, driven to end their lives through the absolute hopelessness of their situations.

Boochani spent five years imprisoned on Manus Island Regional Offshore Processing Centre, or as Boochani more rightly refers to it, on Manus Prison. But No Friend But the Mountains begins even before that nightmare – the story starts with his escape to Indonesia, his multiple attempts to access Australia by boat, and the final boat journey that almost saw him lose his life to the ocean. The absolutely horrific descriptions of the people traffickers, the leaky and inadequate boats, the lack of supplies, the mercenary nature of even the most benign fellow refugees when faced with starvation and trying to protect their families, the complete powerlessness of his circumstances … all of this is traumatic to read, but doubly so because you already know that at the end of that boat journey, he will not find hope or compassion or freedom or welcome, he will only find the stony cold, crossed arms of Australia’s border force as he is refused entry into our country and instead moved with hundreds of others onto the tiny island of Manus. His situation only deteriorates. Manus is described as something akin to a combination of a concentration camp and a gulag. Prisoners are hungry, thirsty, dirty, sick and bored. Food and water are doled out randomly and inconsistently. Phone calls require queueing for hours, as does medical treatment. The tropical heat is almost unbearable, driving the men towards madness. Injuries rapidly get worse in the heat; the bathrooms are filthy beyond belief; even homemade games are banned. The men are treated worse than animals in the slaughter yard. (I was going to say zoo, but zoo animals are treated far better than this).

And yet despite it all, and throughout his ordeal, Boochani somehow manages to not only keep hold of his self-respect and his sanity, but he is brave enough to tell his story to help others, and to share with the world the appalling circumstances that the Australian government would keep from us. No matter what your opinion of the arrival of refugees, by boat or by plane, no matter your philosophy about our borders, you cannot read this book and fail to be moved by the plight of ordinary human beings treated as worthless scum.

Yes, this book is uncomfortable reading, but it is also peopled with memorable and courageous characters. Yes, it is traumatic and disturbing, but it is information that we – as Australians – have a right to know about how our government operates. Yes, it is visceral and painful, but it is also filled with Boochani’s beautiful poetry that somehow lifts the book from despair to optimism. I hope – although I doubt – that every Australian politician has read this book and been as shocked as I was. Buy this book or borrow it from the library. And if you buy a copy, don’t leave it lingering on your bookshelf – put it back into circulation at your local free lending book hub so that Boochani’s message reaches as many people as possible. These are words that need to be shouted; a story that needs to be heard.

‘Do Kurds have any friends other than the mountains?’ I would hope that this witnessing of survival and resistance ensures that all displaced and persecuted people find friendship and open arms in Australia, rather than humiliation, ignorance and discrimination. I hope this is a wake-up call to all Australians to open our hearts to people in pain, and to open our ears and our minds to the policies instituted by our governing officials. Unfortunately we cannot change the past, but we can acknowledge it, sincerely apologise, and take positive steps towards changing the future.