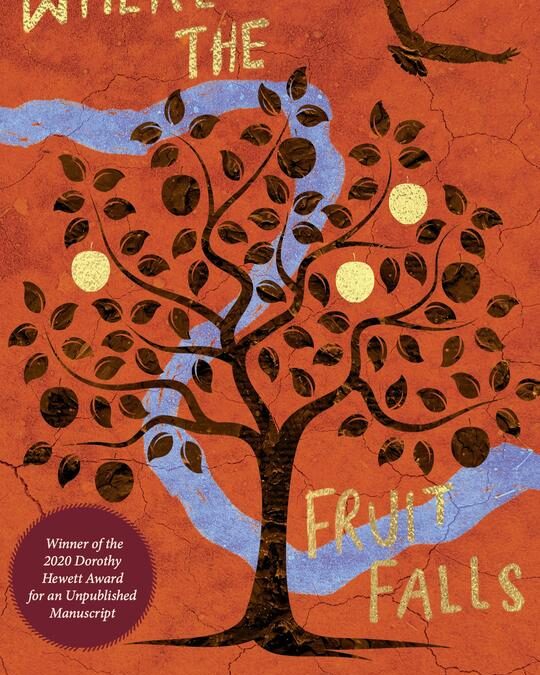

The number and quality of writing published by indigenous authors recently is an embarrassment of riches – so many great novels by both emerging and established writers that showcase Aboriginal connection to country and explore the way in which the Dreamtime and Aboriginal stories are inextricably linked to current events. Somewhere and somewhen; the past at one with the future, the ancestors continuing to speak. Karen Wyld’s book Where the Fruit Falls (UWAP Publishing 2020) is such a book. The winner of the 2020 Dorothy Hewett Award, this saga spans four generations with most of the action taking place in the 60’s and 70’s, a time of social upheaval, with Aboriginal people finally beginning to see some (albeit minor) changes.

The title is a reference to the popular adage and it is true that in this story, similarities run strongly throughout families, whether that be from parent to child, or from grandparent to grandchild. In fact, the entire familial structure, loosely encompassing aunties and uncles, carers and elders, is heralded for its resilience and power, even when disconnection and dispossession tear families apart physically. Women are particularly celebrated, with the narrative featuring several extraordinarily strong and passionate women who are determined to choose their own fates as much as possible.

The story is epic in nature. We meet Brigid Devlin, a young Aboriginal woman, and her twin daughters who travel on a vexed journey. The story frequently switches perspective, such that it morphs into the daughters’ journey, with added points of view from several other characters. This change of perspective perhaps somewhat dilutes the story as we shift from one protagonist to another, but to begin this book is to accept that conventional rules will not be followed, and it is not a linear story with a chronological narrative. As with much recent literature written by Aboriginal authors, the book conveys a sense of blurred edges around time and place, the dead and the living, and relies heavily on metaphor and symbolism. In other novels this might be considered magical realism, but I have come to realise that for a First Nations writer, this is the way stories have always been told, and how they make sense – myths and legends are as real as factual history, ancestors’ voices are as clear as those living today, and the cultural connection to land is a given that cannot be diminished or ceded.

With themes of self-identity, justice, truth, family and resilience, this book is a fascinating insight for anyone wishing to increase their reading knowledge of Aboriginal stories and history.