We met on 1 March, 2014.

When I slipped into the seat next to him at a writing seminar, I had no idea he was a skilled architect, or that he danced the tango, or that his playing of the haunting doina lament was beautiful enough to make you weep. I could have sworn he was in his late fifties; early sixties at the most. I had no idea he was approaching eighty. I had no idea that his charismatic personality would spark an idea that would grow into a character in my next novel, as yet unwritten. Or that three years later I would be sipping lattes with his ex-wife and discussing his remarkable life.

I had no idea that he would choose to end his life because the grey wolf was growling at his ear and snapping at his toes, and he was tired of running.

Ours was a chance encounter. ‘I’m here because I’m thinking of writing my memoir,’ he said. ‘About music and violin, and architecture and tango.’ He wore the colourful clothing of a younger man, a bohemian. His head was bald. ‘Call me Moshlo,’ he said. And I wondered if that was his first name or his last.

We exchanged emails, Moshlo and I. Morrice Shaw preferred to answer to the diminutive name his mother had used when he was small. We emailed about inconsequential things: a workshop I thought he might be interested in; a music clip he suggested I watch. Only every few weeks; only a handful of times. On 4 August, 2014 he wrote to me: ‘I’ve just come home from a month in Turkey; so many stories to be told.’

I replied, but my last few emails went unanswered.

Two years on, and my new work had progressed. A minor character had written her way onto the pages – a Jewish lady who had lost fourteen members of her family to the Holocaust, a homeless woman with a talent for poetry and music, an accomplished violin player who expressed her melancholy through doina. I wrote to Moshlo again: ‘Would you read a short piece?’ I asked. ‘Would you give me some feedback on authenticity, from your own experience?’

I received a reply from a stranger.

‘This is Carla, Moshlo’s ex-wife, writing. I have the sad news for you that Mosh committed suicide last April – just over a year ago. He was plagued all his adult life by depression, anxiety, mild bi-polar…so many diagnoses that in the end just meant he was fiercely talented, passionate and embraced both the dark and the light. He stopped taking his medication and the dark took him.

He would have been so pleased that he was an inspiration for a character in your writing. I’m so pleased too. He was always searching for ways to express the feelings that were inside, whether they were expressed by his own music, writing, architecture or by someone else, it mattered little.’

I was shocked, and saddened. I felt an extraordinary and unexpected grief for someone I hardly knew.

Carla and Moshlo were together for over twenty years, partners in music, dancing, film; in love and in life. Over the next eighteen months, as his estate was finalised and those he cared about were coming to terms with his loss, Carla and I kept in touch as I unravelled the astonishing story of Moshlo’s life, and of his death.

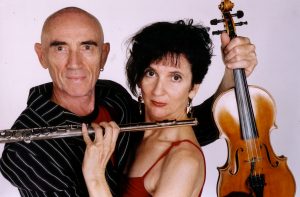

Moshlo and Carla Credit Chris Osbourne

His was a legacy of childhood pain pinned to a framework of intergenerational trauma. He once said that he sacrificed his life for art. Music was an expression of his grief.

Morrice Shaw was born in Poland in 1935. He was circumcised by his grandfather, a Rabbi of some standing, who later disappeared during the conflict. His family immigrated to Australia two years later (before the war, although the menacing grip of anti-Semitism had already taken hold in Europe). His parents, poor but hardworking Jewish migrants, settled in Melbourne in the working-class suburb of Elwood. His father was a furrier who began by adding fur trims to coats, and ended his career in the rag trade as owner, with his brother, of The Shaw Brothers, providing haute couture fashion to Australia’s elite. He dressed the Prime Minister’s wife. The family moved to the upmarket suburb of Toorak.

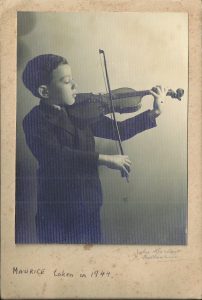

Young Mosh

At the age of five, Moshlo began training as a classical concert violinist. His teacher, intense and exacting, (Moshlo described him as ‘a small, sinister man with a club foot’), tortured Mosh with a demanding, emotionally abusive and punishing regime of practice and performance; Moshlo spoke of ‘working with blood-sweat’. As a teenager, Mosh would sometimes visit his neighbour’s home, the family of the renowned pianist David Helfgott, where David’s father would accompany him on piano. Moshlo and David shared similarly intense and gruelling musical training.

Moshlo’s parents expected him to become a virtuoso violin player. They anticipated nothing less than perfection. At the age of seventeen, he was sent to Paris to study under a master. But in the city of love, he was isolated and lonely. He knew no French; he practised music for up to nine hours each day, determined to make his parents proud. But he was stressed, sickly and thin, and while his violin teacher stretched his musical ability to extremes, nobody was there to make sure he ate regular meals or to ward off illness. His condition deteriorated; he was too sick to leave his lodgings, too sick to do anything but play violin like a man possessed. When a relative finally visited and found him ill and emaciated, ‘bleeding, almost a corpse’, he was returned immediately to Australia, where he was diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease and had most of his ulcerated colon removed. (Nowadays the treatment would involve the less invasive route of medication.) He suffered the indignity of an ileostomy bag for the rest of his life. But of much greater suffering was the shame and humiliation of disappointing his parents; their dream for him had died, and a small part of him had died too. The whole episode was scaffolded in a profound silence, ‘as if Paris had never happened,’ said Moshlo. ‘I never recovered.’

And so, for him, the dichotomy of music was created: at once passionate and enlivening, a zealous fervour, an obsession that would consume his life. But also, in contrast, a tortuous aspiration that could never be achieved, an idea of perfection that could never be reached. Throughout his eighty years, this intensity of music was both angel and demon, both lover and betrayer, as necessary as breathing and as turbulent as chaos.

Carla Thackrah’s early life could not have been more different: she grew up under the sun of Sydney’s northern beaches; her parents were laid-back folk musicians; she studied social work and later travelled to London where she studied post graduate music. When she returned she was appointed Principal Flute for the Australian Opera and also worked for the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (where she first met her current partner, Romano Crivici.)

Initially she and Moshlo met in 1980 through Carla’s first husband, a young architect student who revered Moshlo, his favourite lecturer at Sydney University. ‘His students either adored him and were in awe of him,’ says Carla, ‘or he was mean to them and they detested him; he could be a horribly cruel man.’

‘And yet you say that with a smile on your face,’ I tease. We both laugh. ‘Yeah, well, I suffered the cruelty, let me tell you,’ she replies, ‘but he was an incredibly charismatic character. You’ve got to smile; I think that’s the only reason I survived for twenty years.’

Moshlo, by that stage in his forties, had designed three internationally recognised houses. One day, while collaborating on a building site together on Scotland Island in Sydney, Moshlo was working four stories up installing huge panes of glass when he slipped and fell, head first. The much younger and stronger architect, secure on scaffolding one floor below, managed to catch him by the ankles and his belt buckle on the way down. The friendship of the two men was firmly bonded by this act of fate. ‘My first husband saved the life of my second husband!’ Carla quips.

Moshlo would travel from Brisbane to Balmain in Sydney to stay with the couple, and he and Carla sporadically played music together. While he enjoyed architecture, music was always his first passion.

They lost contact for about five years. Carla was leading a glamorous life with the Australian Opera, ‘dressing up each night and going to after-parties,’ but after eleven years together she and the architect had divorced and she was single and looking for a new relationship.

Moshlo re-entered her life in the most glamorous way. ‘He suddenly burst into my life again. He left me a long message on my answering machine. In French,’ she says. ‘I don’t speak a word of French! I had no idea who it was from.’ Mosh had heard from a mutual friend that Carla was divorced and decided that finally, here was his chance. He later arrived at her house in electric blue jodhpurs and jika-tabi, traditional Japanese split-toe footwear, wearing white aviator sunglasses and a vest that showed off his sculpted muscles, and bearing a huge bunch of flowers. ‘He really wanted to make an impression,’ she says. ‘And it worked.’ Their courtship had begun, and he romanced her in style. ‘He was utterly full on,’ she says, ‘utterly. ‘It was a whirlwind, as narcissists often are. Overwhelming. He flew back to Brisbane, packed up his car and moved in with me.’ Everything happened very quickly and by the end of 1995 the pair was living together in Sydney and performing duets – making music – again. ‘Mosh wanted me as a way back into the music world,’ says Carla. Despite a twenty-year age difference, the couple’s remarkable professional association and romantic liaison blossomed.

Carla and Moshlo Credit Chris Osbourne

I ask about children. ‘No,’ she says, ‘although I would’ve liked to have children with him, and I do regret that, but rather wisely we didn’t. He knew he would have been a shocking father. He was much too self-occupied to be able to deal with kids.’ I comment that it is unusual for a narcissist to have the presence of mind to recognise this in himself; Carla explains that his experience with his own – often absent – father affected him greatly.

Their union was marred almost immediately by Moshlo’s depression and almost crippling anxiety. Only a month after moving in with Carla, a psychiatrist (the first he had ever seen), suggested bi-polar, a diagnosis Mosh had no interest in hearing. ‘And I dismissed it, too,’ says Carla. ‘I thought it was possible, but I didn’t really understand the ramifications; I could not have predicted how bad things would become.’ After one session with the psychiatrist, he did not return (although in later years he would see specialists regularly.)

Frequently Moshlo suffered what he called a ‘crash’; what Carla now recognises were nervous breakdowns or severe anxiety attacks. The first time this happened, not long after they began living together, she arrived home from work at the opera to an empty house. ‘[He was] completely gone. No note, nothing.’ She didn’t hear from him for months, and she had no way to contact him, until he sent a postcard, then eventually returned.

He would often pack up and leave, or demand that she be gone from the house. Moshlo would turn to yoga or meditation, or to a Buddhist or spiritual retreat, to try to return his equilibrium, although Carla says ‘meditation only seemed to make him worse.’

And there were women. Many women. Whenever he had a crash, he would search for a woman who could make him feel good about himself again. ‘This was his pattern,’ says Carla. His previous partner was a well-respected yoga teacher to whom he returned when he needed healing. Carla says she realises now that this is another narcissistic trait. ‘You don’t go to people because you love them, or because you’re attracted, it’s because they have something that you need.’ She pauses. ‘I mean, he loved us too. In his way.’

I ask her what drove him more, the women or the music? ‘That’s a very good question,’ she muses. ‘He was a classic narcissist. He would triangulate,’ she says, ‘he always had a third person in the background, [someone he would] use to get what he wanted out of his primary relationship.’ He triangulated with Carla, telling her she wasn’t as good as his previous partner and she should lift her game, and Carla knows from subsequent discussions with her and other women that this was his modus operandi. He latched on to women and befriended them to help him recover. He loved tango and music because women were attracted to the culture, and therefore to him. ‘He wouldn’t have affairs with them, necessarily, but he would become close to them, zero in on them, talk really deeply …’ She stares intently at me until we both laugh. ‘And I’d watch it and I’d sort of laugh, because it was … really convincing.’ She sips her coffee. I comment that it seems he never really separated from anyone, and she agrees. ‘He would move on, but use that woman to triangulate with the next one.’ The women would each feel tortured by the other women in his life. I suggest that while obviously this was not fair on the women, it also says something about Moshlo, about how he felt about creating bonds with people, and what he felt about breaking those bonds. We talk about this aspect of his personality perhaps being a result not only of his own trauma as a child, but of the intergenerational trauma of his people, and of his family.

Moshlo often described the generational anguish of his older family members. Moshlo’s parents returned to Poland only once, in the sixties. When they visited the village of his birth, the townspeople apparently looked at them and said ‘What are you doing here? We thought we’d killed you all.’ Most of them had indeed been imprisoned at Auschwitz, or in other concentration camps, or had remained in hiding during the war, but incredibly had endured. ‘They were survivors, that family,’ says Carla. Indeed, she often speaks of the condition known as Children of Survivors’ Syndrome as pivotal to understanding Moshlo’s mental health.

Moshlo recalled car trips and family picnics as a boy, with his aunts and uncles raging and crying and ‘telling vile stories’ about the gas chambers of the Holocaust. One uncle frequently opened his shirt and forced Moshlo to bear witness to the scars on his chest inflicted by the Nazis who ‘locked all us Jews in a church and set it on fire’, claiming he was the only one to escape. Carla heard this same story herself, directly from this uncle. ‘That would affect any child, hearing stories like that, and Mosh was a particularly sensitive child.’

This constant background hum of distressing family dynamics, religious persecution and traumatic historical experiences tortured Moshlo. ‘He was empty,’ says Carla simply. ‘He was constantly empty.’ His father was often absent as he worked long hours, and although Carla only knew Moshlo’s mother in her later years, when she was ‘very sweet to me’, his other friends described her as terrifying in her prime. ‘She adored her kids, but they could never, ever impress her.’ Carla recalls Moshlo showing his mother an article in a high-end boutique magazine, featuring one of his architectural designs. ‘“What”, she said to him, “only four pages?”’ She laughs again at the absurdity of the caricature; Carla laughs easily, and finds amusement in what were surely painful times. ‘It was irrational, but he was always looking for approval.’ As an adult, Moshlo became estranged from most of his extended family. He considered them damaged by their tragic past; he found them unpleasant, judgemental and coarse, almost without exception.

Moshlo became unable to cope with the stress of urban life in Sydney, and the couple moved to Byron Bay on the New South Wales north coast, where they stayed for five years, although this time too was marred with his ‘crashes’ and their subsequent separations, with Carla frequently returning to a friend’s home in Sydney. The other women in his life were not the cause of the problems or the crashes, but rather the symptom that he wasn’t coping. His stress was around performing (both music and tango); this would trigger severe anxiety, and he would turn to other women, waiting there in the background, to help him recover by feeding his narcissism. Carla concedes this was a destructive pattern. ‘I hated it. It was horrendous. My strategy was to befriend the women, so that they knew I was around.’ She chuckles. ‘I made some nice friends,’ she says. Eventually she insisted they get married, so that ‘he couldn’t minimise our relationship, or pretend it was nothing, that I was only a shiksa’ (a non-Jewish woman unsuitable for marriage). ‘I knew it wouldn’t change him,’ she admits, ‘but I knew that being his wife, rather than his girlfriend, would make a difference to the other women. And to his family. I figured he can’t minimise the relationship if I am actually his wife.’

‘It’s harder,’ I say, deadpan.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ she says, ‘it’s harder.’

At this point in our conversation, Carla again gives me her infectious laugh as she says ‘I don’t know how you can make a story out of this.’

‘Oh, neither do I,’ I say. ‘Nothing to tell here.’ We explode in inexplicable giggles. Underneath her natural and easy manner, Carla shows a hint of subtle strength, self-possession and equanimity that clearly helped retain her sanity during a troubled and chaotic relationship.

We talk for a bit about the flipside of being close to a narcissist – the many positive and upbeat facets of Moshlo’s personality that Carla adored. Although those close to him, including Carla, could see he was not well, they continued to make excuses for his behaviour, because to live with Mosh was to experience all of the highs, as well as the lows. ‘My theme song was that children’s rhyme,’ says Carla. ‘When he was good, he was very, very good, but when he was bad, he was horrid.’ He masked his insecurity with cruelty, and opinionated exaggeration. ‘The good times were so good, because he was so charismatic, and we had so much in common. We danced tango really well together. We played music really well together.’ But music and dancing weren’t enough.

Over the years, he did eventually see other medical professionals, and was diagnosed by subsequent psychiatrists with various conditions including narcissism, borderline personality disorder and bi-polar, as well as depression and anxiety, although he would not acknowledge most of these labels, and would admit to ‘nothing more serious than depression and anxiety’. He found the truth of his mental illness restrictive; he felt he couldn’t flourish creatively whilst taking medication. ‘It decreased his libido, and he felt less attractive.’ And while he saw many physicians during their time together, Carla says that most seemed reluctant to alienate Moshlo by demanding he accept their diagnoses: ‘It had to be on his terms,’ she says. ‘I think that was the only way to keep him engaged.’ They spent many years in counselling together, and towards the end of his life, Mosh recorded his sessions. Carla describes to me a recording she watched after his death, with Moshlo expounding to his therapist: ‘My women keep demanding I tell the truth. How restricting is that? I can’t possibly flower in my creativity if they are constantly demanding that I tell them the truth.’ She always found herself apologising, in order to ease the tension. ‘It was exhausting,’ she says, ‘but easier than extracting myself from the situation.’

Mosh & Carla perform Woodford Folk Festival 2012 Credit Steve Swayne

The highs and lows continued, like a see-saw. One of the highs for the couple was learning Latin dancing together, eventually reaching semi-professional level. After Byron Bay, they moved to Paddington, in Brisbane’s inner west, while Carla completed her Masters. Their home was known as the ‘yellow tango house’. Moshlo and Carla embraced the joyous melancholy of tango, the sensual rhythm, the ancient beat. Tango became a passionate and important part of their lives, and they passed on this joy by teaching others. ‘Mosh was an amazing dancer. The tango heightened his attraction to women, and he fed off that connection.’ The pair established the tango band, Tango Paradiso, they recorded together and travelled extensively, particularly to Argentina, the home of tango, a city of fading decay yet joyous, intense embrace. His moods were much more stable during this period, as he was taking anti-depressants. ‘They were fantastic,’ she says. ‘When he took them. But of course, then he would feel much better and decide he didn’t need them anymore. And that became the battle.’ Mosh simply didn’t like the idea of medication, and would sometimes take merely ‘a crumb’, even though he knew the meds kept him steady.

‘Very difficult for you,’ I venture.

‘It was fucking horrible,’ she states. ‘How can I explain it? I guess I’m a resilient soul and my relatively trouble-free upbringing enabled me to … I don’t know … I was pretty steady myself.’ One of the psychiatrists Mosh was seeing at the time told Carla that he wouldn’t advocate her staying in the relationship, but if she did, that the only way to be successful in that relationship would be to surrender. To Mosh. ‘And so, a light went on in my head and I thought, I can pretend to surrender, and that’s what I did.’

She would move out when he demanded she leave, then apologise when he called her asking her to return. This capitulation was a sacrifice she made willingly, in order to keep the life they shared. ‘I’m almost embarrassed to say I surrendered because I loved him, but there it is. I loved the life we’d built, and I was miserable when I was away from him. I understood that he wasn’t stable, that his rejection of me wasn’t rational. The middle ground didn’t exist for him – it was either love or hate. When he rejected me, it was a complete rejection into blame and hatred, for a time at least, until he was well again, and then he loved me’ once more. ‘When I think about it now, it’s exhausting.’ She repeats her earlier comment: ‘But it was easier than trying to extract myself.’ I ask her what it was that she got out of it, what made it worth all that effort to stay? Was it the music? Their underlying relationship? It was all of that, she says. ‘We had so much in common, and so many things that we did together, that if I had left, I would have had to give all of that up.’ Ironically, now she has given all of that up, including the tango. ‘I realised it was his dream, not mine. I thought, why am I doing this? I did it for Mosh.’

Mosh & Carla tango

Moshlo and Carla divorced nine months before he died, after an extended two-year separation. Predictably, the final straw came in the form of another woman. ‘I just couldn’t do it anymore,’ she says, and her soft eyes and her thin, dancer’s frame express her vulnerability as well as her extraordinary strength. ‘I had rented a room from a friend in Sydney to use as a bolthole, to give each of us some space,’ she says. ‘He needed this triangulation thing and that became increasingly difficult for me, to see that intensity with other women. I was spending my time between Sydney and our house in Paddington [Brisbane] when he moved his latest girlfriend into our home, amongst all my possessions. He’d never gone that far before. I had twisted and turned around Mosh’s requirements, to keep the relationship together, but that was a step too far.’ Again she laughs at the incredulity of it all. ‘I hadn’t even moved out, I was back and forth to Sydney. He’d obviously told her we had separated.’ I asked her if he had any notion of how odd this was, for her. ‘I don’t think so. Not unless he was confronted with it.’

He was once confronted with the confluence of his two women, at the Brisbane Powerhouse Markets. It had been Carla and Moshlo’s habit to often go together – he would play his violin while a friend played piano accordion, and she would sit with a coffee and listen, do her shopping, or sometimes accompany him on flute. On this particular day, she went to the markets and had the surreal experience of seeing this other woman sitting there, in her spot, having a coffee, in thrall to his music, like seeing a mirror image of herself. ‘He literally replaced me. It was so bizarre. I watched her walk up to him and kiss him on the cheek, and off she toddled. Then he saw me, and he came over to me, and I blasted him, and that was one of the only times I think he realised, shit, that might have been awful for her. But most of the time he didn’t get that, or if he saw it, he didn’t care.’

Carla’s current partner, Romano, a composer and musician wearing a colourful embroidered tarboosh, works quietly beside us during the interview, interrupting only occasionally with a chuckle or a playful quip – he knew Moshlo for over forty years and is only too aware of the emotional rollercoaster the couple rode. He reminds Carla of the phrase Moshlo would frequently shout: ‘I will not be thwarted!’ He demonstrates Moshlo’s expression, his facial features screwed up tight, his hands clenched into fists. ‘I will not be thwarted!’ He used these words, Carla says, in relation to everything from women and music to relatives and work. When I ask what he meant by that, her reply is simple. ‘He meant ‘this is how it is.’ That is all.’

Moshlo and Carla communicated every day, despite the presence of other women in his life. ‘I really knew him,’ she says simply. Romano interjects: You are too modest, he seems to say, touching his lips to hers. And what he does say is: ‘He was totally dependent on you.’ It seems true that Moshlo was still reliant on Carla to the very end of his life, despite their divorce.

I move the conversation back to the doina, the musical form about which I was ignorant until I met Moshlo. The first time he heard doina, the mystical, trance-like music reignited a memory in Moshlo’s mind of the lullabies his mother sang to him as a child in Poland; the subconscious sounds of his past. The gravitas stirred him. It was his description of the haunting lament (the klezma, the ‘Romanian Blues’), and the video clips he sent me – dark, grainy, black and white montages of flickering candles and sinister shadows with the strains of evocative, melancholic music – that first sparked my imagination, and created the building blocks for the character in my novel. What of the doina? I asked.

‘Mosh had never spoken of an affiliation with the Jewish religion,’ says Carla. ‘In fact, at times he was almost anti his own Jewishness. Orthodox, Ultra-Orthodox … He understood politics, but he was not a Zionist. The situation in Israel disturbed him. He felt great empathy for the Palestinians. And yet, whenever he met another Jew, he felt an immediate affinity. He trusted that person. He held a profound and deep distrust for people generally, even friends. He used to say ‘you could betray me at any time’, even to me he would say this.’ But in Byron Bay, he bonded with the alternative Jewish scene, and Carla was always astounded to see him instantly connect with another Jewish person. Ironically, it was an Italian man – George – rather than a Jew, who introduced him to the doina when he was well into his seventies. ‘He was blown away. He became obsessed, and deeply moved by the doina; he felt the lament rang true. He could feel his own sadness in the music.’ As with everything he did, Moshlo followed through with boundless energy. He travelled to Israel for a few weeks, then went to Berlin where Carla joined him. While dancing the tango in Tel Aviv, he met a woman named Beatrice at a tango milonga (social dance) who happened to know something about doina and the spiritual intensity of the music’s inner searching. Beatrice introduced him to Mendy, a man Moshlo would later describe as his ‘brother’. At the time, Moshlo emailed Beatrice that meeting Mendy was ‘a triumph of chance meant to be’. Mendy owned an alternative bookshop nestled in a dungeon in an old bunker in Tel Aviv; a Centre for Yiddish culture containing hundreds of old Yiddish books. In a missive to Carla, Moshlo wrote: ‘So once again the serendipity of the moment led me to a remarkable series of encounters … this concrete bunker has endless concrete corridors with empty shops, and would make a perfect set for a post Kafka Armageddon movie … so finally I get to do the Jewish number. YES it did feel very special and wonderful. I had an immediate connection, even to the bearded ones, but NO, I will not be moving to Israel !!! It kindled something inside me nevertheless, stirred the DNA, and has made my sojourn here very worthwhile. Mendy and I have become brothers, he is a remarkable man and very very delightful. Charming and full of mischievous energy … we are on the same page as they say. You see how connections arrive in their own unique ways?’

And to Beatrice he wrote: ‘I had only a vague idea of something growing inside me and needed to be said. It was in a way a treasure hunt, and you turned out to be one of the beacons. That’s the mysterious way of such chance meetings which of course are not chance but fate.’

Mosh & Paul Hankinson recording Doina Berlin 2012

Mendy gave Moshlo the gift of transcriptions of doina into notation. The dark sense of foreboding of the place they met – the bleak dungeon – echoed the shadows of the music they played. Moshlo subsequently went to Berlin, where he recorded doina in yet another subterranean space; a studio deep underground, the pockmarks from hundreds of bullet holes still lining the roughened walls, a grim reminder of the war. Carla joined him and they began to record together. ‘He was a perfectionist,’ she says. ‘He would spend hours in our apartment practising one simple turn or ornament, going over every bar mindfully. But it shows, in the way he recorded those doinas: they’re beautiful. He didn’t embrace the Jewishness of it but he embraced the feeling. He was terribly empty and insecure, but this – the doina – filled him up.’

Moshlo and his piano accompanist, Paul Hankinson, a ‘brilliant musician’, practiced over and over in the war-ravaged concrete bunker. Mosh would perform ‘hundreds of takes until it was exactly as he wanted it to be’, then Paul would record an accompaniment separately. Fittingly, they practiced and recorded just across the road from the biggest flak tower of the war, from where the Germans shot down Allied planes, and also across from the dungeons where SS Nazi soldiers tortured countless Jews.

Yet despite this intense practice, the performance of doina is not precise like the playing of modern violin; the tones slide from one note to another, searching for the right resonance. Rather than playing a precisely notated musical score, the doina calls for improvising around the notes, which allows the performer to express their own individuality and feeling in the music. This is what gives the doina its unique sound.

Mosh and Carla in Berlin during recording

‘We got obsessed with all the war stuff,’ says Carla, ‘because it matched the music he was playing at the time. This was the only bunker left … most were filled in after the war because they didn’t want them used as shrines to Hitler, but this one was forgotten about and only discovered not so long ago. The setting was so evocative of the music, and Berlin was the perfect place to do it. It was one of the best times we’d ever had’ she says, ‘we enjoyed each other’s company and had a great friendship. I knew he was still a crazy man, and I had to tread carefully, but he no longer held the emotional power.’

The doina provided a respite that resonated with a deep, generational familiarity.

But it was not enough.

‘I have tidal waves of despair, I can’t take this any longer, and I thought, the best thing to do now, is just to surrender, and to surrender my life, completely.

And so I tried to kill myself. You know, in my life I think I feel that a grey wolf has been shadowing me. Suddenly it began to pick up speed, the wolf was panting and I could feel its breath, it was hot on my heels, I always felt that it wanted to consume me.

Another wolf, literally eating my entrails, the pain, and while it was there, eating the residue that they’d cut away from me. I managed to spring away from him … and I’ve been sprinting ever since, I was at the finishing line … things can’t go on forever. I can only say that everything, finally, has to come to an end.’

Extract from Last Portrait of Moshlo

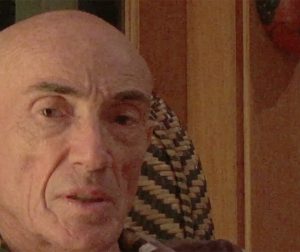

Mosh one week before he died

By January, 2015, four months before his death, Moshlo’s depression and anxiety had become steadily worse. Although she was communicating with him every day, it was only later that Carla discovered that he had stopped taking his medication nine months earlier.

He began to panic more frequently. He fell and fractured a vertebra. He felt frail. He no longer wanted to cope with the debilitating incursion of his illness, or with his intrusive black thoughts. He felt he was losing his edge, losing control, that his beauty was fading and his body was failing. He was mourning the loss of himself. He called and emailed her constantly, leaving long messages, and declarations of love. He was, he said, exhausted.

‘I had seen him go through this so many times, but he always came out,’ says Carla. This time was different. He went back on his medication, but ‘the wrong ones, and it took a few weeks to realise they weren’t working. He was very down.’ He sent Carla (in Sydney) an email telling her he loved her, that they had shared an amazing life together, but that ‘this is the final curtain and I can’t take it any longer.’ Carla called a Brisbane friend to check on him, to find that Mosh had sat for three hours in his car in his garage, with a bottle of champagne, breathing the car exhaust through a tube from the running engine. He was hospitalised, and Carla immediately flew back to Brisbane. She moved into his house to care for him, and was there when he was allowed home on weekends. It was, she says, ‘the worst I’d ever seen him. He’d lost a lot of weight, crashed. He couldn’t take in nutrients … nothing life-threatening but everything to him felt like it was going wrong.’ He had made a serious attempt at suicide, and was dismayed that he failed. Perhaps to himself he intoned his mantra that he would not be thwarted, but outwardly he assured his friends that he would not try again to take his life.

It was during this time, and at Moshlo’s request, that Carla made a short film – a poignant, moving piece – The Last Portrait of Moshlo, in which he talks about his life and his pain; his extreme exhaustion; his grief and his depression; the grey wolf pursuing him, snapping at his heels; his desire to surrender to the wolf, to end his life. He trusted she would portray him authentically. This is her specialty now: portraiture in the digital age. Portraits not of traditional paint and canvas, but of film and sound. Short and affecting visual snapshots that reveal a person’s own view of themselves.

For a short time, it seemed Moshlo had stabilised. He still spent much of his time in the hospital; he was taking his medication. Even his psychiatrist thought he was doing okay.

But the perfect storm had arrived.

He waited until Carla left for a brief visit to Sydney. During his weekend day release, a mutual friend was living with him and housekeeping in Carla’s absence. Usually they went to the markets together, but on this particular day he said he didn’t want to go. He was too tired, he said.

He was determined not to be thwarted.

Mosh at the end of his life 2015

The friend arrived home after shopping and assumed he was downstairs sleeping. When she went to wake him for lunch, she found a note at the top of the stairs, warning her not to go any further, and asking her to notify the police.

His last attempt at shielding his friend failed, as the triple O operator instructed her to search the house. She found the worst possible scenario.

Moshlo had tried to slit his wrists in the bath. When that had proved too slow, he had hung himself in the laundry.

Carla has obviously gone over this experience many times with her friend, and is distressed as she recounts the facts of his suicide, his careful planning. She shakes her head. ‘Once he decided something, he would see it through to the bitter end. He’d decided he didn’t want to live anymore. He was playing his favourite flute music and drinking champagne. He [often] called me ‘his champagne’, and both times he had champagne with him when he attempted suicide.’ She looks wistful. ‘That’s nice. And also not nice. What can you say? That’s the dismal end.’

She shares with me the poignant detail that when he was found, Moshlo’s feet were hanging down in the perfect ballet dancing position, almost poised, which is ‘apt, because he adored dancing.’

Perhaps he departed this world by dancing on to the next.

‘That man, I lived with his suffering. I knew how desperate he was. I experienced his desperation. I saw how he suffered, mentally, late at night when he paced because he couldn’t sleep. I get why he did it, and how determined he was. He was not going to be thwarted, even in dying.’

He left Carla eight suicide notes, written a month or so before he died. He writes of being unable to cope with his physical deterioration, combined with his anxiety. In them he speaks not only of his own physical pain and mental anguish, but his guilt, ‘that he was not as nice as he could have been’, his deeply embedded sadness. When he died, he left out on his desk, as if on display, a certificate and medallion from the Surf Lifesavers, thanking him for his generous support. ‘As if he was trying to make amends,’ Carla says. ‘As if he was saying, ‘Look. I am a good man.’’

And yet to so many he was a good man. To his ailing parents in their final years, to the women in his life, to his many friends, to musicians with whom he collaborated and composed and performed. Like so many of us, he was both joyful and dark, both light and shadow.

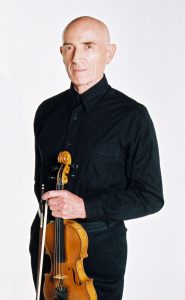

Mosh Credit Chris Osbourne

The morning he died, he left a note on his treasured violin, addressed to Carla and Romano, asking them to care for it and, when they felt ready, to donate it to the conservatorium in perpetuity, to be lent each year to a student who otherwise might never experience playing music on such a beautiful instrument. Light and shade.

Moshlo bequeathed nearly his entire estate to the charity Medicines sans Frontiers, a legacy which appeared to disappoint his immediate family. Inexplicably, Carla bore the brunt of this disappointment during the two years after his death; a settling of the estate that was drawn out and distressing. Carla was unable to retrieve the personal mementos that meant so much to her: photographs, recordings, small tokens of the life they shared. In this way, his death somewhat mirrored the tortuous struggles of his life.

At the end of our time together, Carla and I are both simultaneously exhausted with the telling, and invigorated with the reliving of those tumultuous years of suffering and desperation, of passionate joy and furious intensity. She says she is stronger now, that she has more emotional resilience. I am glad. She seems a very balanced person, with an energy and vitality that belie her years of life experience. The estate is finally settled, the house sold, the proceeds distributed to various charities and Moshlo’s loved ones.

Their intertwined life created enormous joy and terrible sadness; that dichotomy again, of light and dark.

I reflect on chance encounters, on how one story leads to another, on how our lives are linked by the infinitesimal minutiae of living, and the vast infinity of consequences.

Last Portrait of Moshlo from carla thackrah on Vimeo.