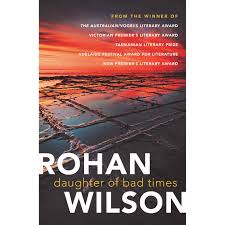

Rohan Wilson’s newest novel Daughter of Bad Times (Allen and Unwin 2019) is that rarest of literary creations – a page-turning, completely immersive plot combined with a simmering undercurrent of subtext and meaning that delivers a chilling message about our times. This is a book that is well-written in every aspect – taut writing, compelling character development, a thrilling plot, authentic dialogue, imaginative and detailed world-building, and threaded throughout, the exploration of contemporary themes.

Set in 2075, the story is so realistic that it seems prescient rather than merely futuristic. The world has changed, not only through great advances in technology but by the tragic effects of climate change and consequent global events, including an horrific tsunami, which has resulted in whole nations being submerged, and most other countries struggling to keep the sea at bay. The obvious consequence of this is the overwhelming number of stateless refugees – people displaced by natural disasters, with nowhere to call home and no country willing to offer asylum. But with spine-tingling familiarity to our own current tragedy of offshore detention centres, the twin interests of politics and big business have stepped in to profit from others’ misery.

Eaglehawk MTC is a manufactory operated by giant conglomerate Cabey-Yasuda. Situated in Tasmania, the company offers stateless refugees the possibility of a visa to Australia if they participate in a 12-month work commitment. (Sound familiar?) Desperate people, many of them environmental refugees, survivors of the tsunami tragedy that killed their entire families, are willing to believe in anything that offers the faintest glimmer of hope for their future.

Rin Braden, the daughter of the company owner, hates working for the corrupt system of Cabey-Yasuda but feels she has no choice, especially after her depression when she fears that her lover, Yamaan, has been lost to the disaster. But when she learns that Yamann is alive and being held in an immigration detention facility, she is desperate to save him. The choices she makes, however, have dire consequences not only for Yamaan and for Rin’s mother’s company, but for the secrets of Rin’s past that come to light.

The epistolary narrative is interspersed with court transcripts, media reports and letters from subsequent legal investigations after the conclusion of the main story, thus providing the reader insights into the aftermath whilst still being immersed in the action.

What I loved most about this book was its compelling comparison between the hellish vision of the future and the issues we face today. Climate change, refugees, wealth disparity, vanishing resources, the privatisation of services, the collection and use of personal data – all of these things are happening in today’s world. Rohan Wilson extrapolates what is already happening into a violent and shocking prediction of the planet in 2075, which – we should remember – is only just over 50 years away. Like The Handmaid’s Tale, that future looks grim, but lifting the story from abject horror is the tender and wise portrayal of human connections – parent for child; lover for lover; friend for friend – that capture small moments of optimism amongst the horror.

The opening scene is a particularly fine example: Yamaan’s friend Hassan, in the midst of his imprisonment in Eaglehawk, insists on imagining and describing the possibility of his young son being able to live for weeks, perhaps months, at the top of a coconut tree. The poignancy of this rather strange image is not obvious until later when we realise that only those at the highest points would have been able to survive the tsunami. Hassan’s hope is a small flame, and yet it persists; it is perhaps all that is keeping him from total despair. The story is carried forward by these small but powerful vignettes of humanity.