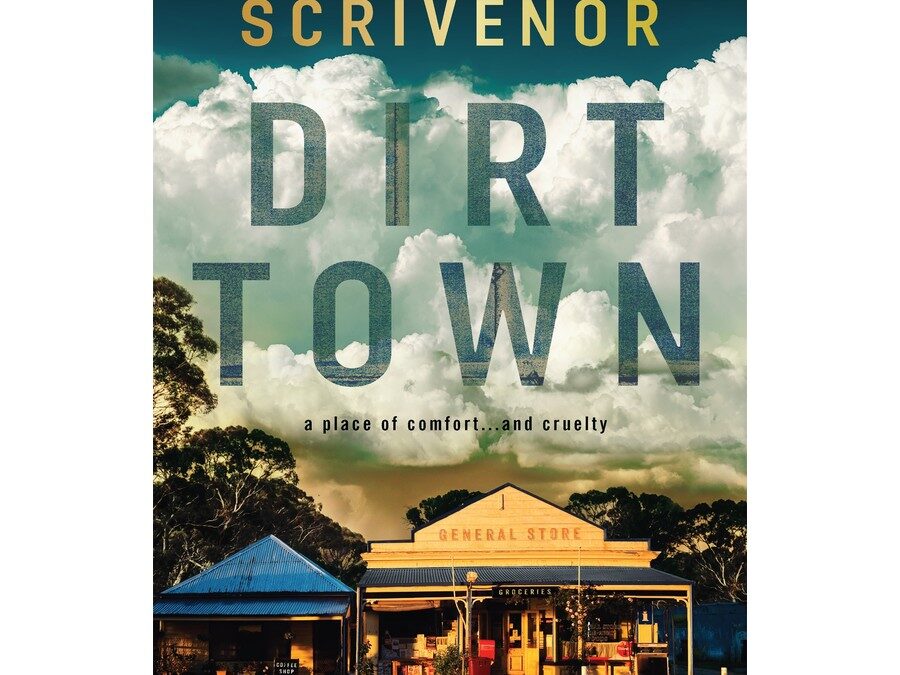

2022 has been the year for amazing debut crime novels by female Aussie writers, especially those writing outback noir or focussing on the intimacy and intensity of small rural towns. One such novel that has already garnered heaps of accolades is Hayley Scrivenor’s Dirt Town (Pan MacMillan 2022), an earlier version of which was shortlisted for the Penguin Literary Prize and won the Kill Your Darlings Unpublished Manuscript Award.

For crime lovers, there are many familiar themes in this story. Best friends Ronnie and Esther wave goodbye to each other on one ordinary day after school, but Esther never makes it home. Ronnie is determined to find her, with the help of their friend Lewis. But Lewis holds a secret that terrifies him and keeps him from being entirely honest during the search. The featured cop in the story, Detective Sergeant Sarah Michaels, is brought in from the city to lead the investigation. She has her own private demons and is very aware that people can be driven to desperate acts, completely out of character, through extraordinary circumstances.

The entire story takes place over only a week, so every day is filled with the intense minutia of the investigation and the thoughts and deeds of everyone associated – potential witnesses, suspects and victims of other crimes, if not this particular one. The chapters are from alternating points of view, which allows the reader into the heads of more than one main character.

But there are two things that make this story stand out. The first is that in the opening chapter, by page three, we (the reader, although not the other characters) become aware that Esther is already dead. This is an interesting revelation because the story then becomes not about whether she might be still alive, but rather what has happened to her and who is involved in her disappearance and death. In this book, the reader knows more than the characters, which adds a complex perspective to the subsequent investigations.

The second highly original construct is that the chapter points of view include one titled ‘WE’, interspersed throughout the novel. It is at first unclear who the ‘we’ is meant to be, but it is obvious it is a collective ‘we’, and that it is something to do with the town itself, the community, the very fabric holding Durton (or Dirt Town) together. As the novel progresses, this ‘WE’ becomes more complex and nuanced, and the final chapters from this perspective tie together the whole notion of a small town community, where everybody knows everybody else and their business, where rumours are rife, legends become lore, and the crimes and critical incidents of the town are embedded in the community like the rings of a tree, marking important events that have changed or affected the town over the years. This perspective is very clever structurally and lifts the story onto another level.

The characterisation is rich and detailed, and the depiction of life in a small town is evocative and nuanced. The reader is kept guessing until the very last page as to the details of what exactly happened to Esther, along with other tangential plots and themes that have been woven into the story. The book traverses some complex themes of family violence, diversity and the legacy of trauma, neatly threading these issues through the main plot with a subtle and restrained hand. The power of lies and why we tell them, even to ourselves, is explored in a genuinely refined way. I highly recommend this complex and thought-provoking novel.