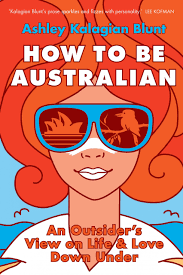

What an absolute delight to read a book that is funny, self-deprecating, honest, sharply observant, curious, indignant, tender, thoughtful and thought-provoking. How to be Australian: An Outsider’s View on Life and Love Down Under (Affirm Press 2020) is a memoir by Ashley Kalagian Blunt about her relocation to Australia from Canada and her experience of acclimatising (physically, socially and emotionally) to a new country. It is life-affirming and quirky; it is laugh-out-loud hilarious as Ashley and her husband Steve naively and blunderingly adapt to the eccentricities of Australian life.

Ashley was a seasoned traveller and had spent long periods – years – living in Asia, South America and Europe. The decision to spend a year in Australia was mostly based on her being fed up to the back teeth with the relentless cold of her home city, Winnipeg. How hard could living in Australia be? It had endless sunshine, strange animals, and the locals all spoke English; so they relocated to Sydney.

The first half of the book is a wry summary of misunderstandings, mispronunciations and misadventures with wildlife. Barefoot people boarding trams in the middle of the city, indecipherable coffee, ibis (bin chickens) sneaking ‘through the grass with ginger steps like they were leaving the scene of a crime’. Cockroaches the size of small mammals, intimidating spiders, and the filthy share houses that every Aussie uni student has experienced. Biscuits covered in ‘what looked like an elderly person’s pubic hair’, and rather unfortunately called ‘iced vovos’.

The second half of the book, whilst continuing to be highly entertaining through Ashley’s keen eye for the absurd, the ridiculous and the incomprehensible, drills down into a deeper layer. Her husband Steve is unable to find work and they both find the stress of adaptation difficult. Ashley swings between unhappiness, desperation to fit in, mental fragility, torn feelings about whether or not they have made the right decision and a nevertheless unending curiosity about the place and the people they are living amongst, all while trying to study and write a book.

This book traverses some even more serious themes. The author is well aware of her privilege in being able to choose to live in Australia, and to eventually apply to stay here permanently. She is conscious that is a choice not available to many others. She finds it difficult to accept her new country’s treatment of refugees and, equally, of the Indigenous population. All this is happening while she’s writing a book about her Armenian great-grandparents and the struggles they survived as exiled people; the irony is not lost on her, and in fact only opens her eyes even wider to the political and cultural situation in Australia. There is a whole section about cultural cringe and the hypocrisy and confronting facts of Australia Day (or Invasion Day), and the government’s ‘blatant human rights violations’ in their detention of asylum seekers. Ashley acknowledges, respects and honours First Nations peoples in various ways throughout the story.

The couple are undecided: to stay or to go? To apply for permanent residency or to return to family? To relish in a kookaburra’s laugh and the vista of the Sydney Opera House or to suffer through attempting to conquer Cradle Mountain and the taste of Vegemite? At one stage, she says: ‘Maybe if you couldn’t find a home, you could make one.’

And alongside their struggle to understand and fit in to their new country, they are encountering their own personal difficulties as they realise that they want different things, and they respond to stress in very different ways. Ashley worries too much, wants too many hugs (‘not possible’), drinks water too fast and uses terrible sunscreen. Like all recently married couples, the first years are a tricky navigation of compromises and empathy.

Eventually they negotiate their way through the interminable Australian residency and citizenship bureaucracy. They travel across the country in search of what it means to be Australian, from Tasmania to Western Australia to the Northern Territory to North Queensland. In her trademark understated way, she says of the NT: ‘In the Dry [season] … the humidity eases and the temperature lowers, and it’s more suited to popular activities such as breathing’. And her wonder at the marvellous ridiculousness of the front pages of the NT News is breathtakingly refreshing.

Battling homesickness, the urge to keep travelling, anxiety, worries about her marriage, and her own mental state, Ashley sets out to understand this country – Australia – that she thinks they might like to call home. Sometimes memoirs can risk being twee, trite or overly sentimental, but this book is none of those things. Rather it is a frank self-examination of the author’s motivations, failings, failures, desires, hopes, dreams and uncertainties, written with a critical eye (towards both her home countries and herself), and underpinned by a thirst for knowledge that ensures the writing is fresh and new. While I’m sure this book will be familiar to migrants and visitors, it is also a fresh look at our country for those of us who were born here – its highs and lows, its achievements and embarrassments, its bland derogatory manner and its fulsome optimism. I thoroughly enjoyed every moment of this easy-to-read, delightful, funny and heart-warming memoir. (And it reminded me a bit of Margot Margolyes’ recent TV series, Almost Australian).