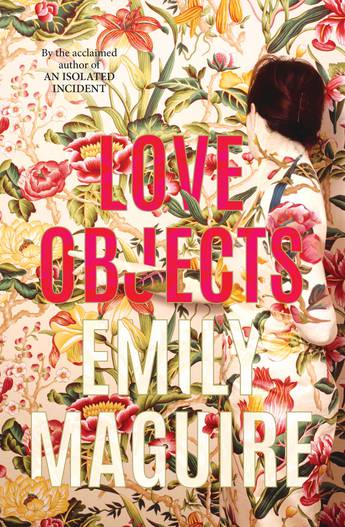

Love Objects (Allen and Unwin 2021) by author Emily Maguire, is graced with a stunning cover by designer Sandy Cull and artwork by Cecelia Paredes: a gorgeous profusion of flowers with a woman hidden in plain sight in the riot of blooms. You would be right to begin judging this book by its cover. Maguire has ostensibly written an accessible and highly readable story about a hoarder but as the novel progresses, it becomes obvious that it is about so much more.

In the hands of such a skillful writer, an ordinary life and banal circumstances are elevated to a deep introspection about familial bonds, loss, grief, betrayal and the role possessions play in filling up the empty spaces in our lives. It becomes a portrait of class as we gain ever widening glimpses into the situations of the characters – what they can afford, the decisions they must make to buy x over y, the choice to walk rather than catch the bus because that will mean an extra can of home-brand tuna, the fact that a rich girl can still look rich in second-hand clothes and grunge, but a poor girl in the same outfit just looks poor, and possibly homeless. It is about generational classicism; about expecting to be no better than your parents, and to have no more than they had, while others live in mansions and drive new cars and tip outrageously and give no more thought to whether they can afford food as to whether they might fly to the moon. The themes in this book are so wide-ranging and yet so deftly examined, and the characters so perfectly presented, that we become completely engaged in these people’s lives and very invested in the outcomes for every one of them.

Nic is 45, single, the most wonderful aunt to Lena and Will, a saviour of neighbourhood cats, an amateur nail artist and locked in a never-ending battle with her sister Michelle. Nic is also a hoarder (not that she would ever acknowledge that). She has decades’ worth of newspapers, bags and bags of new clothing bought from Kmart, pens and towels and fridges and sewing machines and gadgets and doohickeys and wigwams. She has SO MUCH STUFF. The most interesting thing about Nic and her precious belongings is her attitude towards the personal (used) items, whether they belong to her or have previously belonged to somebody else. Obviously she treasures her own ephemera, paraphernalia and collectibles…they are her memories made visceral. The red shirt she was wearing during an important kiss, a scrap of hair from her niece, a cookbook bought in the hope of preparing a meal for someone special. But it is her love for the objects of others that is really fascinating. She cannot pass by a single shoe, a hair ribbon, a doll’s bonnet, a figurine, a chair, a vase without imagining the life that object had before she obtained it, how much it was loved and used. She can picture the child holding the doll, the woman on a date wearing the shoes, the bottom that sat in that chair for years, the fresh flowers that used to grace the vase. She simply cannot bear that these objects have been separated from their owners, or worse, thrown away as unwanted and unloved. She feels an obligation, a duty, to take them in and care for them, to place them together with other scattered objects and to create a kind of family where nobody is alone and or lonely, in a place that feels safe and secure and comforting. She feels safe and comforted surrounded by these objects. They fill some deep need in her for belonging, for normality, for hope that one day she might allow others in to share her precious finds.

But of course that will never happen. On some subconscious level, Nic understands that her home is not open to visitors or to scrutiny. She babysits at other people’s houses but never in her own home. She has a weekly lunch date with her beloved niece Lena but always at a restaurant. Lena – the relative to whom she is closest – has no idea how bad things have become. She pictures her aunt Nic as she knew her in her childhood, with a welcoming home always ready for her and her brother to stay.

But one day, when Nic doesn’t show up for their regular date, Lena travels to her aunt’s house to make sure she’s okay. What she finds will shock both of them, and lead to uncomfortable and confronting days and weeks for them as they wrestle with the aftermath of the discovery.

Emily Maguire is known for her feminist writing and one thread of the story is woven tightly around the idea of consent, female desire, double standards for men and women, the culture of toxic masculinity, and the endless shame associated with sexual assault. It would be a spoiler to say too much about this aspect of the book, but the storyline that runs through the narrative on this topic is confronting, very timely, thought-provoking and heartbreaking.

The characters in this book launch from one catastrophe to another. Most of them live from day to day, in permanent survival mode. It is easy to forget that that is how life is for so many people, those who live in poverty or who are unemployed or suffer mental health issues or who are socially isolated or disadvantaged. They are simply getting by, from one difficulty to the next. And the overarching feeling of this novel is the compassion that we, as readers, feel for those characters and the situations in which they find themselves, whether or not they are of their own making. We understand their difficult decisions, their paucity of choices, their lack of agency. Maguire truly enables us to see through their eyes, and to comprehend the enormity of facing challenges when you have neither the resources nor the support nor the energy to be up to the task.

This is a book of tragedy and need, of desire and want and emptiness and brokenness. But it is also full of sparkle and wit, with funny dialogue and heart-warming relationships, with passion and tenderness and humour and trust and connection and belonging. It explores self-identity and shame, and the dynamics of how people struggle and cope, with a wise insight and a gentle and compassionate eye.