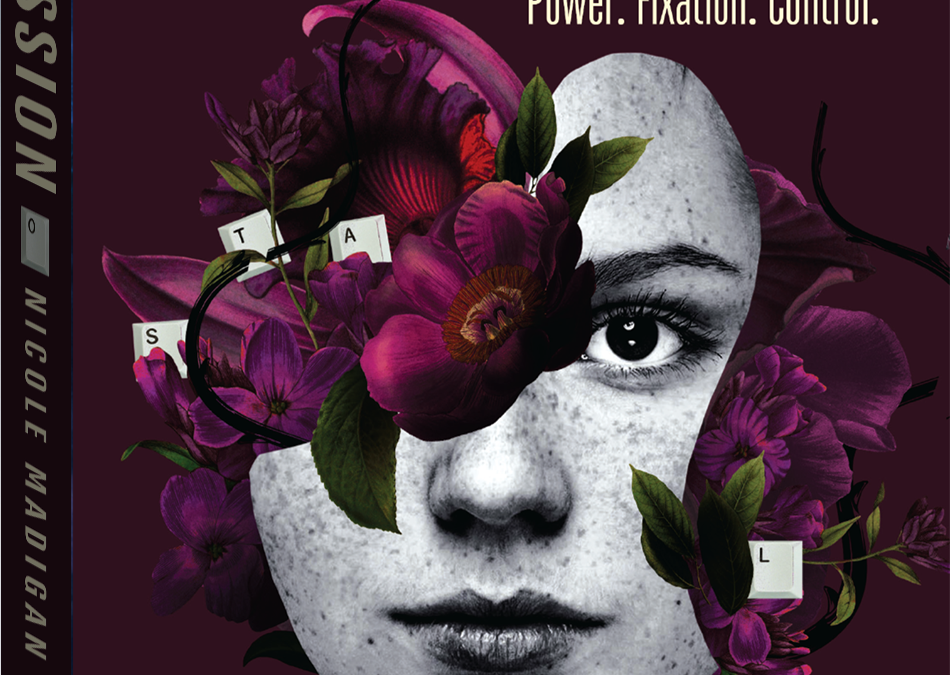

Nicole Madigan is an investigative journalist and writer, and her book Obsession: A journalist and victim-survivor’s investigation into stalking (Pantera Press 2023) is an absolutely unputdownable non-fiction book that reads with the page-turning suspense of a novel but is scaffolded by statistics, real cases and information about police and legal procedures. This is Madigan’s personal story, but she has widened her examination of this subject to include media reports, police action (or inaction), legal avenues, legislative changes, case studies, the effects of stalking on victim-survivors and even the perspective of a stalker who spoke openly about his experience. This is a book that will open your eyes, or – if you are a victim-survivor yourself – validate your emotions.

Madigan explores lives that have been dismantled by the relentless pursuit of the obsessed, causing fear, torment, anxiety and helplessness, often exacerbated by being dismissed or disbelieved by the police, the justice system, society and even friends and family. She investigates what drives perpetrators to torment others. The book contains traumatic themes including rape, suicide and mental illness and a warning that this may be distressing.

But it is also ultimately a book of hope for change, validation, understanding and justice.

As with a fictional novel, it would be a spoiler to divulge too much detail about Madigan’s own case. Her experience is threaded throughout the book, interspersed with other information which supports her own difficulties. I will say that the stalking began when she was particularly vulnerable during the breakdown of her marriage of 12 years, and that – certainly surprisingly to me – it was a female stalker that wreaked havoc in her life. This person exhibited just about every single behaviour that we read about in the media, which resulted in Madigan feeling every debilitating emotion that we also read about. Because she has personalised the experience – in chilling, abhorrent, disgusting, frightening detail – and then connected that to the experiences of others, the result is a horrifying account of the toll a stalker can inflict. But because we are also allowed to read the end of her story, we are shown the changing reactions to stalking, and a glimpse of hope and empowerment.

Obsession is a beautifully written story that explores a traumatic subject with grace, dignity, honesty, vulnerability and a determination for change.

Obsession opens with some myths and mistaken beliefs about stalking, the rates of reported stalking versus arrests and convictions (and the addition of unreported stalking). She begins her own story; she tells of her anger, shock, fear, sadness and impotence as a result of the vulgarities, obscene language, lies and threats to which she was subjected. She confronts what all victim-survivors must face: if I ignore them, will they get bored and go away? If I report them, will that aggravate the situation? How far am I prepared to let this go? Am I overreacting or underreacting? Stalking ruins lives, reputations (both personal and professional), threatens physical safety and endangers mental and emotional wellbeing. Why should MY personal life – my interests, my job, my social media contacts, my daily activities – be changed; isn’t it right that the perpetrator must suffer consequences, rather than me altering my life?

The multiple behaviours that fit the stalking profile include continuous contact, approaching family and friends, public defamation and the spreading of lies. The difficulty is that we care about what people think, and so are therefore less likely to report problematic behaviour for fear of embarrassment, shame or being accused of overreacting. Self-esteem plummets when our appearance, our partner, our family and our interests are constantly attacked and belittled. The immense relief of finding out that the stalker is a serial offender (they have similarly abused others) or that other people have suffered similar stalking experiences is tempered by the fact that the offence continues to occur, and that it is so incredibly difficult to do anything about it. The humiliation, the anxiety of receiving hundreds of posts or hashtags or letters or phone calls or even direct contact, is debilitating.

Some people, such as Clementine Ford, have responded by openly naming and shaming offenders and calling them out publicly for their behaviour, but does the potential downside of this outweigh the benefits? Erin Molan campaigned for legislative change regarding online bullying and trolling. Others such as Ginger Gorman, Bri Lee, Jess Hill, Grace Tame and Stephanie Wood exposed ‘dark secrets with searing honesty by examining all perspectives’, a commitment which Madigan found ‘profoundly important’.

Madigan refers to research such as that by Professor Paul Mullen, who has studied stalking for over 40 years, defining it as ‘repeated unwanted communication or contact, in a way that would cause apprehension or fear in most people’. She examines the spectrum of stalking behaviour, from what might seem ‘mild’ to the most dangerous of all, which ends with murder. This escalation from stalking to violence is interrogated. She discusses the choices victim-survivors make regarding either deleting evidence of stalking behaviour because it is so distressing, versus keeping a digital record to be used as evidence, and how an early choice is crucial to what might occur later.

All stalking is obsessive and entitled but the motivations and behaviour behind stalking can be very different. Madigan provides statistics and anecdotal examples to support her investigation. She discusses the five types of stalker: The Rejected Stalker (often after the breakdown of a relationship); The Intimacy Seeker (who longs for a relationship; this is entangled with erotomania – the delusional belief that another person, usually of a higher social status, is in love with them ie the celebrity stalker); The Resentful Stalker (seeking revenge or retribution); The Incompetent Suitor (seeking short-term gratification spawned by loneliness or lust); and finally The Predator (less common but a more serious risk – the deadly and chilling attention of a stranger). She deconstructs how all of these perpetrators impact or restrict someone’s life in so many ways.

Other topics include the difference in gender attitudes, the line between love/loyalty and obsession, mental health, religion and the importance of a Victim Impact Statement (VIS). In fact, Madigan includes her own VIS at the end of the book, and it is an extremely powerful document; she states that connecting with others is empowering, validating and comforting.

Stalking causes psychological harm and major damage to people’s lives. They feel voiceless. The lies told are endlessly imaginative and damaging (revenge porn, negative online reviews, identity theft, public commentary) and can lead to loss of employment and financial instability, marriage breakdown and family estrangement. Madigan examines common red flags and discusses our modern reliance on technology and the internet as being a ‘stalker’s dream’. She interrogates the depiction of stalking in movies and literature, how both victim-survivors and perpetrators are portrayed, common misconceptions, the dangers of spyware and the challenges to dealing with stalking. She includes #LetHerSpeak and #MeToo. Victim-survivors want the stalking to stop but they also want justice. Stalking is surprisingly widespread and Madigan’s story of over three years of distress induced by somebody who devoted a huge amount of time and energy to harassing and threatening her is frightening.

Madigan states: ‘Victim-survivors are the change-makers. So are the families of victims who didn’t survive. By channelling their own pain and torment, they are the people who change community attitudes. They change laws. They save lives.’ This is an important and revelatory book.