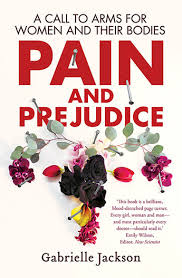

Journalist Gabrielle Jackson was first diagnosed with endometriosis in 2001 and after writing about her experiences in The Guardian in 2015, and subsequently being overwhelmed with emails from other women who had suffered similar experiences, she focussed her interest on how women’s pain is treated in our modern healthcare systems. The result is her non-fiction book Pain and Prejudice (Allen and Unwin 2019), a brilliant and powerful examination of how the pain and suffering of women are treated in our own culture and around the world, how little is known about ‘women’s illnesses’, the bias towards male-centred medical research, and the continuing myth of ‘hysterical’ women labelled as such because their symptoms and pain cannot be explained.

In a seamless blend of memoir and investigative journalism, Jackson confronts this issue from the historical to the modern, with a rigorous and intellectual interrogation of medical culture and practice, peppered with plenty of real-life anecdotes and examples from her own experience and from women she has met in the course of her work.

Labelled ‘the silent disease’ because nobody knows how to talk about it, or wants to talk about it, endometriosis is only the tip of the iceberg. Jackson explores the ten chronic pain conditions that most specifically or often affect women, including Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Chronic Migraine, Chronic Tension-Type Headache, Interstitial Cystitis, Fibromyalgia, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Vulvodynia, Temporo-mandibular Disorders, Chronic Low Back Pain and Endometriosis, and investigates how these debilitating conditions frequently overlap and are often misdiagnosed or even ignored. She discusses the lost opportunities, lost employment or school days, the failed relationships and general ill health suffered by women as a result of this failure to recognise and effectively treat women’s health. She argues that ‘for most of human history, the widespread idea that a woman is inherently irrational and brimming with uncontrollable emotions and bodily functions has justified her subordination’ and she laments the lack of knowledge around female body parts and their functions, even the incorrect language commonly used – often by women themselves! She reveals numerous examples of how women’s pain – throughout history – has been minimalised, trivialised, ignored or mistreated.

Covering everything from Aboriginal women’s health to the #MeToo movement, Jackson talks about how ‘racism, poverty, violence, trauma, abuse and stress all contribute to poor health, and women suffer disproportionately in many of these areas’, and discusses the links between anxiety and depression and poor physical health.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Jackson summarises her investigation by exploring the advances made in women’s health, and highlights some of the promising research and funding opportunities. Perhaps most importantly, Pain and Prejudice opens a frank and open discourse about women and their bodies, and urges everyone – men, women and medical professionals – to have informed conversations with each other and to vigilantly pursue improved women’s health.