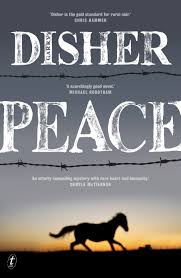

When Garry Disher won the Ned Kelly Lifetime Achievement Award, he was described by the Australian Crime Writers Association as ‘a giant not only of crime fiction but of Australian letters’. With over 50 titles published across multiple genres, he is best known for his rural noir – gritty crime novels set in the Australian outback. His latest book Peace (Text 2019), a follow-up to his popular Bitter Wash Road, again features Constable Paul Hirshhausen, banished after a scandal to running a one-cop station in the tiny community of Tiverton in the Flinders Rangers.

Hirsh is a blow-in – he’s only been in town a year – but he is finally starting to get to know the locals and to earn some grudging acceptance and respect. He turns up for community working bees, and travels long hours on dusty roads to conduct welfare checks on lonely or vulnerable people living on isolated farmsteads.

Mostly his days are long, banal and predictable – some graffiti on a barn, a stolen power tool, neighbours complaining about noise. But it is the lead-up to Christmas and as the heat is building, so is his workload. Two boys steal a ute, he has a grass fire to deal with, and a local woman decides to ‘enter the front bar of the pub without exiting her car’. The local sticky-beaks are taking photos and voicing their complaints and Hirsh is doing his best to keep calm and cool. All of this is the backdrop to what is to come – a terribly brutal and strange incident on a property in town that has everyone scratching their heads, and the big guns from Sydney police asking about a family living on an isolated back road on the fringes of town. Hirsh is immersed into the investigations of several crimes, which he realises have their roots much deeper than the little town of Tiverton.

Garry Disher writes very engaging small-town characters, full of flaws and foibles; everyone knowing everyone else’s business, or choosing to comment on it even if they don’t. His protagonist Hirsh, demoted after the embarrassing city business, is endearing – plodding along, trying to do his best, sometimes failing, always aware that he is letting someone down. At one point, when someone asks him whether he thought to bring leather gloves, he thinks: ‘No, Hirsh hadn’t thought to bring leather gloves – or any kind of gloves. His life was full of things he hadn’t thought to do, and things he knew he ought to have done.’ The dialogue is outstanding, perfectly pitched and sharp; Disher has a finely attuned ear for the disparate voices in the novel. And he has a very droll sense of humour.

Disher is a master at understatement, describing a landscape and people with great detail and then throwing in, almost as an afterthought, the fact that he can also see a gaping wound or evidence of a gunshot or some other act of violence. And the plot is everything you would expect from a good crime novel – some horrifying opening incidents that draw you right into this world, a slow burn of investigation, suspects, victims, clues and possible motives, and a successful resolution at the end, while leaving plenty of scope for further books in this series.

An interesting addition is the journal or diary entries of Mrs Elizabeth Keir from the mid 1800’s, which he discovers and are then interspersed throughout the story, mostly deriding the ‘natives’. These passages highlight the past and its connection to the contemporary.