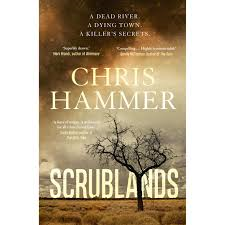

Journalist Chris Hammer’s crime novel Scrublands (Allen & Unwin Books 2018) burst onto the scene with a lot of fanfare as an addition to the genre ‘outback noir’, which includes books such as Jane Harper’s The Dry.

Much of this categorisation is related to the setting: Scrublands is set in the fictional town of Riversend in a drought-affected area of inland Australia; the days are unrelentingly hot and the land is parched and dry. Almost every chapter describes some aspect of the heat, and the sense of a half-deserted or abandoned country town struggling to survive despite the elements is authentic. As a crime story, Scrublands has a lot going on. The complex narrative begins a year earlier, when local priest Byron Swift calmly opens fire on his parishioners outside his church, killing five men in cold blood. The local cop then kills the priest, and the town is left to mourn and recover. A year later, journalist Martin Scarsden, himself the victim of a recent traumatic event while working in the Middle East, is sent to the town of Riversend to file a follow-up story about how the locals and the town are faring on the anniversary of the tragedy. But the information Martin begins to uncover doesn’t seem to fit with the facts outlined in his newspaper’s award-winning feature of 12 months previously. As he gets to know the locals, he is given conflicting stories about the priest, the shooting and the victims. At this point, the narrative becomes far more complicated and, as with any good crime story, there is a whole host of characters with backstories, motives and opportunities, any of whom could be suspects, victims or both. And if they’re not guilty of one thing, they might be guilty of something else. The plot thickens when the bodies of two backpackers, missing since the shooting, are found in a local dam in the scrublands. The media of Australia descends on the small community and Martin finds himself not only at the centre of the tragedy, but personally involved, as he discovers more and more information, and forges links to some of the locals. The plot is ambitious, with many sub-plots and connections, and although Hammer manages to tie it all together by the end, I did find some points coincidental or a little far-fetched (Martin uncovers enough secrets and lies to fill three books!)

But there are many things this book does well. One is the mirror the story holds up to journalist Martin Scarsden’s own behaviour, and the questions the novel asks about the role of investigative or frontline reporters and their motivations. The truth is not always pretty, and one suspects that as an experienced journalist himself, Chris Hammer has had a lot of time and probably much lived experience to inform his contemplation of these issues. And that career also serves the content of the book well, bringing a ring of authenticity that comes directly from Hammer’s journalistic background. The way the reporters approach the story, the hierarchal directions from above, the communication between rival journos, the engagement with locals, the push to file before deadlines, all of this is not so much expressed, as just there, woven into the fabric of the story, and it feels real and true. Hammer does great dialogue and really captures the personalities that inhabit the lonely towns of inner Australia, and he has done a great job of giving each character – from a very large cast – their own backstory and history. And finally, the novel asks some important questions about PTSD and military service, ambition and reputation, familial sacrifice and the legacy of traumatic events.