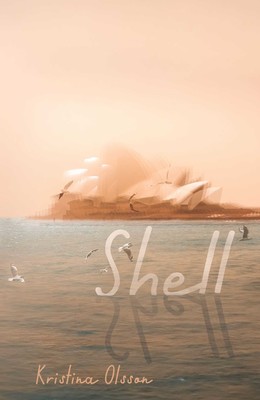

From the very first pages of Shell (Scribner Books 2018), the new novel by Kris Olsson, you realise you are in the capable hands of a masterful storyteller. Not a word is wasted. Each sentence is crafted with care. Every paragraph sings from the page, like poetry, like prayer. The story is meticulously researched, and that research informs every line of dialogue, every cultural reference, all the minutiae of daily life. The characters are fully formed and multi-faceted; each has a background that is hinted at but never thrust upon us, each is complex and nuanced, never black and white. The themes of the book: family and community; war and service and sacrifice; belonging; guilt and morality; politics; atonement; art and creativity – all are explored with sensitivity and thoughtfulness. This is a rare kind of book, one that is so well written that it is surely destined to become a classic of the Australian literature canon.

The story is set in Sydney in 1965, with two narratives braiding together the lives of Pearl Keogh and Axel Lindquist. Pearl is a young journalist who has been relegated to the ‘Women’s Pages’ because of her anti-war stance. When conscription becomes fact, and 20-year-old boys are being drafted for the Vietnam War, Pearl becomes obsessed with trying to protect her fractured family. Alex Lindquist is a master glassmaker from Sweden, commissioned to create a centrepiece for the new Opera House which is under construction. But with the vision of Danish architect Jorn Utzon clashing with the financial and social restrictions of the government of the day, and Sydneysiders divided over their views of the strange construction as either an ugly eyesore and waste of money or an inspired and magnificent cultural wonder, tensions run high amongst union workers, politicians and artists. It is these two major conflicts – the uproar over the war and the consternation over the Opera House – that mark the times and define the lives of the characters.

As with all of Kris Olsson’s works, Shell was informed by historical aspects of her own life, nuggets of pain or rage or devotion or regret that she has used as the stepping stones on her search for answers. She says in the Author’s Note that ‘Ideas and notions and doubts coalesce into a long and intricate conversation with myself…’ and that ‘The more I write, and read, and the older I get, the more comfortable I am with uncertainty. With being the humble servant of the questions, the story.’ This wise statement comes from a place of deep reflection, from a writer who ceaselessly strives to uncover truth, and who is never complacent about the meaning of what she discovers.

I could quote passages from Shell, luminescent and shimmering words, but there are so many it is difficult to choose. The entire book is poetic, each line lingers so that even after you have read on, you find yourself returning to the previous section, just for the thrill of reading it again, purely for the beauty of the language. The book plunges us into the lives of Pearl and Axel and carries us as their journeys intertwine. We are first intimately engrossed in one and then with the other, and all the while the social and political acts of the time are enshrouding these two people like a caul. There is plot – and it is tense and compelling. There is dialogue – and it is authentic and believable. There is the familiarity of the setting and the majesty of the architectural creation and the despair and fear of the looming war. There is the chaos and the impossible choices and the irresolvable intricacies of family. But above all that, there is the language. The beautiful, lilting, descriptive language that holds us aloft as we progress through the story. Every line I read was magnified in my mind and I could hear it, each line, read by Kris’s careful and steady voice, the novel narrated as a song would be sung, as a mantra would be chanted, as a prayer would be spoken. This story is unforgettable, and this book is a marvel.