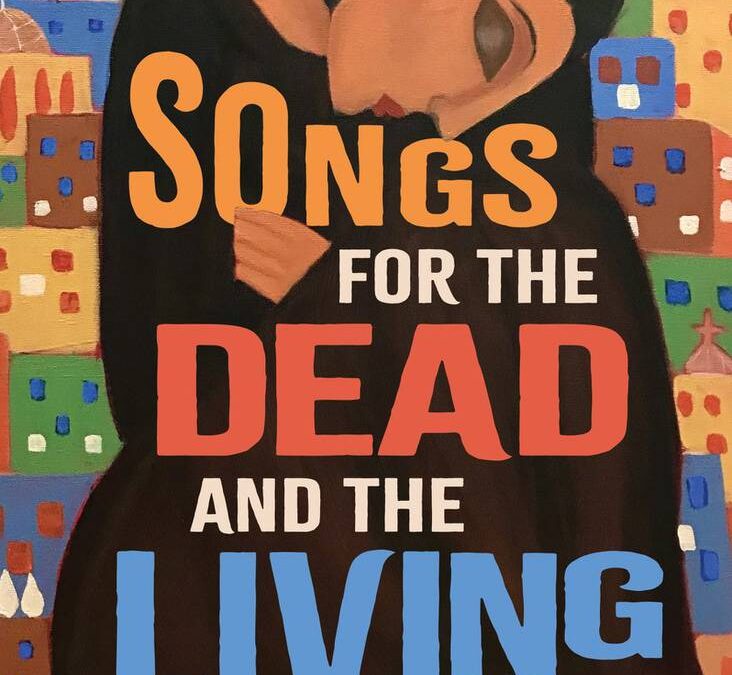

Songs for the Dead and the Living (Affirm Press 2023) is a pertinent novel for our times. Written by Sara M Saleh, the daughter of immigrants from Palestine, Egypt and Lebanon, the author combines her personal experiences, the history of her family and her skill in writing poetry to create this debut novel about belonging, family, loyalty, fear, racism, outsiders, escape and the idea of Home.

At the centre of the story is Jamilah who lives in Beirut with her extended, noisy and sometimes chaotic family. The novel is set in three times and places: Beit Samra in Lebanon from 1977 – 1982; Cairo in Egypt from 1982 – 1985; and Sydney, Australia from 1984 – 1986. Jamilah’s idea of Home shifts precariously throughout this time, as she learns her family are Palestinian refugees blending in to Lebanese society, then fleeing to Cairo to escape conflict, and finally landing in Australia, knowing she may never really know where to call Home, or ever be able to truly return.

The novel captures the essence of what it’s like to grow up in a war-torn nation, to be ‘outsiders’ in the land of your birth because of your family’s history, to be forced to make difficult choices, weighing up all you might leave behind with all you might gain by moving forward. The current conflict in this area of the world makes this book all the more relevant – set over 50 years ago, it seems very little has changed and perhaps has only become worse.

The cast of characters is large and initially there is a complexity to the family situation which does take some time, as a reader, to get your head around. But gradually we become familiar with Jamilah, her sisters, her parents, her extended family and her friends and neighbours, and we see that life is indeed complicated not only by their situation but by their cultural and familial bonds and responsibilities. Love and desire blossom but are tempered by duty, respect, expectations and situational difficulties.

I felt the author really hit her stride with the last third of the novel, which is urgent, pacy, intense and authentic, and which certainly brought together all of the earlier writing. The resolution or conclusion in the epilogue was especially satisfying.

In the first part of the novel, there was perhaps a little too much ‘info-dumping’ for my liking – explanations of cultural and societal norms, and background political information – but then in the end, I was grateful for it as I was mostly ignorant of the details and the minutiae of life in Lebanon and Egypt at that time. It was necessary information but could perhaps have been delivered with a lighter touch.

The author’s poetic background results in some beautiful, lilting, lyrical prose, and she delves into personal, familial, cultural and societal complexities with compassion, wisdom and a good dollop of humour which definitely lightens the story.

This is a book that imparts information in a highly readable and empathetic way, and asks the reader to consider connection, belonging, exile, love and duty on both a personal and wider, community scale.