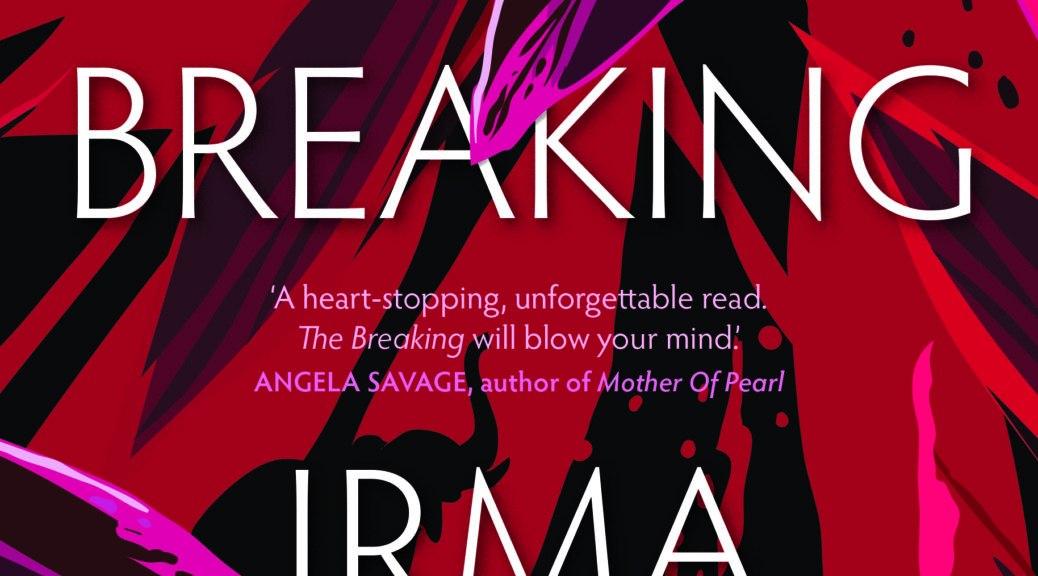

Irma Gold’s novel The Breaking (Midnight Sun 2021) is a confronting, heartbreaking, visceral, bold and unforgettable story of the link between animal tourism and horrific cruelty, told through the perspectives of two young women with passion, heart and vision.

It was only about halfway through that I understood the layered meaning of the title, and it perfectly depicts the story within.

Hannah Bird is an Australian newly arrived in Thailand, keen to immerse herself in the culture and escape from difficulties at home. She is disoriented by the uncomfortable reality of life in a less-developed country, where families struggle to survive, and will do almost anything for the tourism dollar. She meets Deven, a feisty and determined expat who has settled into Thai life and decided on the road less travelled. Deven abhors the tricks and trinkets of tourism and rather than be part of the problem, she yearns to be involved in the solution. The two friends are caught up in an elephant rescue organisation, which seems to be achieving great progress and change, and which satisfies the girls’ moral and ethical questions. Or does it? As Hannah and Deven become more deeply exposed to the true state of animal exploitation, the high demand of foreigners for ‘traditional’ experiences and how far locals will go to provide those experiences, for a cost, the young women become increasingly disillusioned and uncomfortable with how things are done. And yet … they are not part of the system or the culture, and they don’t understand or have to deal with the financial worries of the locals. Their privilege becomes more and more obvious. And no matter how hard they try to ‘help’, their privilege remains a stumbling block to true understanding and their ability to fully participate and to comprehend the totality of the obstacles the locals face.

Gold’s lived experience is very obvious as having informed the intimate details of this novel. The sounds, smells, sights and tastes of Thailand are depicted as only someone who has travelled there could describe them. This is true also of the ethical dilemma explored around the issue of poverty in less developed countries, and what local people might be prepared to do to survive, often at the behest of wealthier foreigners, and frequently for activities, products or services that are not available unless you travel overseas. This was an issue also delicately explored in Angela Savage’s book Mother of Pearl, which examined overseas surrogacy in a similarly sensitive way.

Gold uses local language and casual references to food and culture in a way that expects the reader to keep up, rather than spoon-feeding them with explanations or forced background. That said, there is a lot of detail included that the author has clearly experienced herself. There are also many visceral and uncomfortable details included, of animal trauma, brazen tourist exploitation of local people, poverty forcing families to make difficult choices and well-meaning outsiders trying their best to right what they see as wrongs, but which ultimately are beyond their understanding.

Alongside the narrative of the elephants is the story of self-identity, coming-of-age and female friendship between Hannah and Deven, also explored with compassion, humour and understanding. I found I engaged more with Hannah (as the narrator), and really felt for her feelings of being lost and intimidated while travelling, misunderstood and uncertain at home, and tentative and shy around Deven.

Some books you read because of the information they impart. The Breaking is one of those books – I felt deeply affected by the insight I gained into an industry I realised I knew little about. And that is what sets this apart from other novels about Australian travellers experiencing a foreign country: the deep and lasting impression of connection and feeling for animal welfare and what might be done to ensure boundaries are not crossed while still ensuring cultural integrity and basic human needs are met.