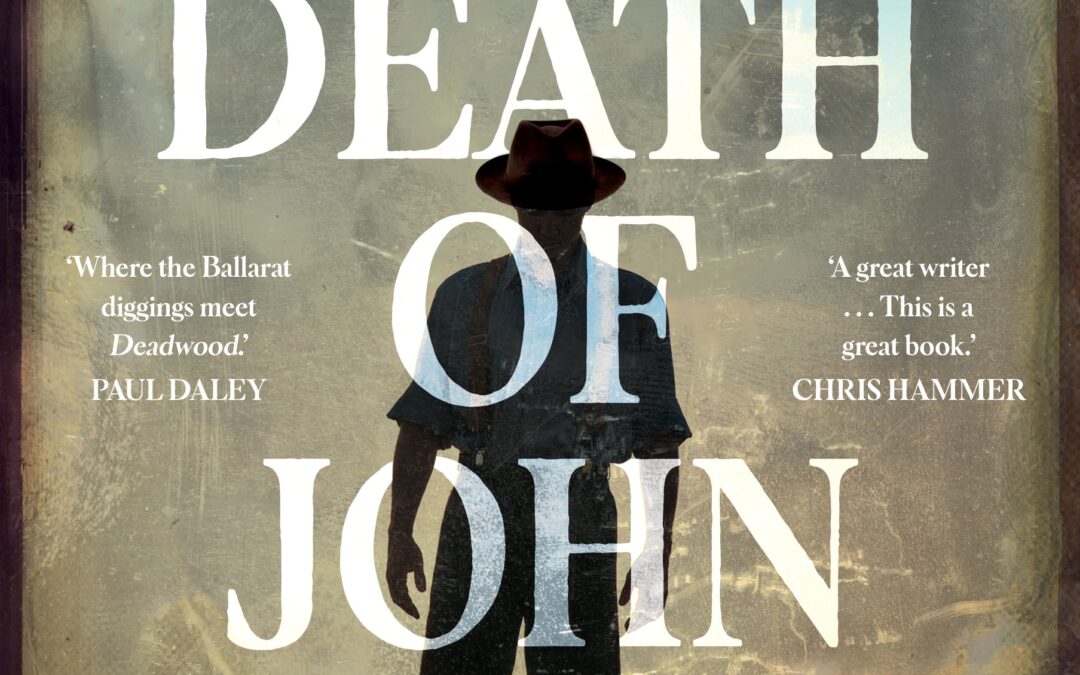

Author Ben Hobson writes about men, boys, mateship, family and violence. Those are recurring themes in all three of his novels so far. His latest book The Death of John Lacey (Allen and Unwin 2023) revisits those themes but incorporates much richer, complex and nuanced notions about right and wrong, morality and duty, revenge and redemption. This novel also demonstrates Hobson’s writing trajectory – his other books are good but The Death of John Lacey is excellent writing on a whole other level. The language is spare and sparse, the dialogue spot-on, the historical setting authentic and the story absolutely compelling and driven.

The story concerns two sets of brothers and the events that bring them together. Set from around 1840 to 1870 in the young settlement of the Ballarat gold fields, life is harsh – conditions are difficult, brutality is common and peace (physically or emotionally) is hard to come by. Hobson immerses us completely into that space with his visceral and shocking descriptions as if he has a hand around our collective throats and slowly squeezes until we feel we cannot breathe.

The death of the title occurs on the first page, which has the most poignant closing sentences: ‘He did not regret that he had killed the boy. He regretted only he had not killed him so hard he had stayed proper dead’. The tone then shifts to 23 years earlier, with brothers Ernst and Joe Montague, and the main narrative begins from their childhood and continues until their circumstances on the run from the law, and as is revealed, when they end up in the town of Lacey. This is where the two families’ stories, that of the Montague brothers, and of the Lacey brothers, Gray and John, intersect; John Lacey founded the town and he rules it with an iron fist. Nothing happens without his knowledge; nobody does anything without his permission. It is peak wild west lawlessness. The book is divided into sections about these four men and also about Gilbert Delaney, a local preacher who plays a crucial role in the story.

A book set in the colonial Australia of the 1800’s could not fail to include the dispossession of First Nations people and the way Hobson has incorporated the tragic truths of our country’s history is raw, shameful and traumatising even to read. I am not Indigenous but to me the incidents he depicts and the circumstances he describes feel not only authentic, but almost like a non-fiction account of the times. In a very important Author’s Note in the front of the book (and I’m so pleased he acknowledges this before the story even begins), he writes: ‘…I have endeavoured to represent the attitudes of the early colonialists as accurately as possible, including their use of derogatory terminology and the expression…of harmful ideas. However, it is important to acknowledge that these attitudes and beliefs are in no way acceptable by contemporary standards.’ He then goes on to thank the Wadawurrung people, with whom he consulted, for the use of their language and research and resources while writing this book.

This is such an important issue, one which could easily go very wrong, but like balancing on a tightrope, Hobson has managed to not only vividly depict the brutality, the prejudice, the trauma, the wrongness, of the times, but I believe he has done so from a place of purity of intent: he genuinely feels rage at our country’s treatment of First Nations people and he expresses that (in an opposite way) through his characters’ actions, words and thoughts. Again, it’s like reading a history book or an early colonialist’s journal – he does not shy away from the horrific attitudes of the time, but he also manages to make it very clear (through both the story and the characters) that this period was a shameful and reprehensible time, that we should all know just how truly horrendous it was, and that through that knowing, we should – we can – do better today. Acknowledging that history is vital to understanding the trauma inflicted on Aboriginal people, and why that trauma is still carried now, generations later. I admire his bravery in confronting this issue with a defiant and steadfast gaze.

I also commend him on his writing of violence. This book is full of violence, as was our land at the time, but Hobson retains command of his pen and every event he depicts is terrible but necessary. Not once did I feel the violence was gratuitous or overdone. It is not often you read a book so terribly violent that you finish with such a sense of redemption and peace.

And the reason for this is that Hobson balances the atrocities with a nuanced moral conversation that asks many questions of the reader. Family is at the heart of this book, as with all his novels, and the love, loyalty and sacrifice of family, especially brothers, elevates the book into a different space and allows the reader moments to breathe, to reflect and to feel joy. There are so many ethical quandaries here, and the reader will switch allegiances and experience inner conflict along with several of the characters as they face crucial life choices. Our own moral compass is tested.

The book races to an extended climactic conclusion which has all the hallmarks of a great thriller or crime book but retains its literary language and the sense of teetering morality as we balance on that tightrope. Hobson maintains control of this section with perfect pacing and we are drawn along towards the end wanting to turn every page faster but also fearful of how the story might end.

While I connected with the characters, engaged with the story and appreciated the historical setting, it is the writing itself that I most admire in this book. It’s gripping, gritty, raw, powerful and unflinching. It has a certain spare, clipped style that denotes an experienced writer who has studied his craft and worked very hard to make it seamless. The other highlight for me is that the novel explores shame, regret, revenge, trauma, friendship, sacrifice, love, loyalty and family, but most importantly of all, compassion, mercy and justice. The capacity for humans to act in a compassionate way amidst the burning hell of a violent and brutal landscape shines through with grace. The characters all have to make difficult decisions, but as a reader, I also found myself questioning every scene, every incident, wondering what I would have done in their place. I’m sure The Death of John Lacey will evoke many robust discussions at book clubs.

This is a novel that will make you think, seriously, about our collective past, and whether fiction, rather than history books (written by the ‘victors’) might more accurately reflect the trauma and truth of our past.