The Hope Fault (Fremantle Press 2017) by Tracy Farr is a literary fiction novel of almost faultless breathtaking imagery and emotion. In a bay in Cassetown, an extended family gathers to unmake their home – a beachside house, once meant as a retirement escape, but due to life’s circumstances, long since rented to strangers. But now it has been put up for sale, has indeed, been sold, and the family has come together to pack and sort, and to remember. Iris and her ex-husband Paul, their son Kurt, Paul’s new wife Kristin and their baby (as yet unnamed), Paul’s twin sister Marti and her daughter Luce, gather for one last hurrah. Not physically present, but nevertheless a significant character, is Iris’ mother Rosa, 100 years old and residing in a nursing home.

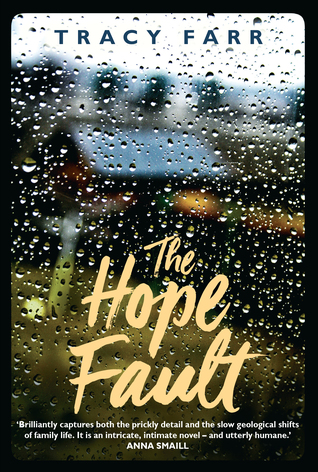

It is a simple and unlikely cast (Paul and Iris get on remarkably well considering their situation), and the story too is simple – nothing much really happens, and yet everything is changing. What drives the narrative forward is the slow and intimate recording of family life, the pace of growth and change, the individuals that make up this family – their hopes and plans, their secrets and their truths, all set against the backdrop of the relentless barrage of rain that sluices down gutters and wipes clean the landscape, providing a watery stage for every interaction.

The prose in this book is a joy to read, the descriptions are vivid and sensual, the landscape and environment exposed and bare, the weather and the elements raw and primal. The sea, the rain, the bush, the evenings, the dead of night…all are depicted with such presence, such force, such minute capturing of detail, that we feel we are there, in that house by the sea, listening to the storms, sheltering inside the home’s strong arms.

The entire book is set over one weekend, and what this demonstrated to me was the incredible emotion and feeling that can be packed into a novel based purely on family dynamics and relations. Plot here is not only incidental, it is unnecessary. There is so much going on in the interior lives of these few characters that we don’t need any extraneous detail. I kept expecting something ‘big’ to happen, but when it didn’t, I was not disappointed. The characters are enough. The house is enough. The rain is enough. And in fact, the lack of external factors emphasises the importance and significance of the myriad of small details of the human experience which each of us live, every day.

There is one clever and unusual device inserted into the middle of the novel that gives us a wider perspective: a calendar of Rosa’s life, spinning backwards over the past 100 years, allowing us to glimpse, little by little, flashes of her life as an old woman, as a grandmother, as a mother, as a young woman, as a child. The structure of this section is short, sharp and again, very vivid and meaningful. We have spent the first third of the book with a handful of characters over a couple of days; suddenly we flip through 100 years of a single character; and then we spend the last third of the novel back with the same handful of characters, again over little more than 24 hours. The difference, of course is that we now have the knowledge of Rosa’s experience; she has come alive for us through letters and memories, through poems and stories. And although she is not physically present in the house, the ripple effects of what we learn of her life touch our understanding of all those within.

I imagine this story would be a joy to read out loud. The prose is almost like poetry, but also like science, and like a song, too; imagery and language all stitched up together in an enviable rendering of family life that celebrates the joys and connections, that mourns the losses, and that seeks to comprehend – in small, still, quiet ways – the very essence of existence.