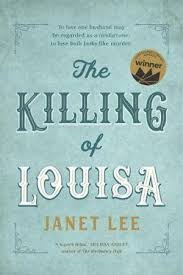

The Killing of Louisa (UQP 2018), a reimagined retelling of the true crime case of Louisa Collins, the last woman hanged in New South Wales in 1889, won the Emerging Author category in the 2017 Queensland Literary Awards for writer Janet Lee. This is a highly readable book, with simple language and short chapters, exactly befitting the distinctive voice of Louisa, from whom the story is told in the first person. Louisa is a woman of her time – educated to only a low level, married at a young age, and birthing 10 children over a relatively short period – and yet hers is a voice that reaches out beyond the 130 years since her death, and speaks to the reader of a life that is easily conjured despite it being vastly different from today.

The case of Louisa Collins is well-known, the details of her fate are officially recorded, and several previous books have described her life and the trials which came to end it. But it is testament to the author’s skill that despite knowing the outcome of the book before we begin, the narrative is nevertheless compelling and engaging. Louisa was born into a relatively poor family and was sent out to work as a domestic servant while still a teenager. Her marriage to her first husband, Charles Andrews, who was 15 years older, was arranged by her parents when she was only 18. She bore him nine children and they lived a hand-to-mouth existence, mostly scrabbling to get by on Charles’ income as a butcher and later as a carrier, while Louisa took in boarders and cared for their family. Two of their children died in infancy, as was common in those days. But it was the following series of events that caused people to take particular notice of Louisa: the illness and unexplained death of her husband, Charles; her hasty second marriage to boarder Michael Collins and the subsequent death of both him and their son John; the details surrounding Charles’ life insurance policy; and the box of Rough on Rats found in the house. Louisa was tried on four occasions for the murder of one or other of her husbands; on the fourth occasion, she was found guilty and sentenced to hang, partly due to the evidence given by her own 10-year-old (and only daughter), May.

With her conviction recorded, and her imminent death, Louisa tells the story of her life to the prison chaplain, and so reveals her early life and childhood, her family of origin, the circumstances of her first marriage and the births of her children, and the situation that led to her second marriage. These chapters of personal reflection are interspersed with clippings from newspapers and court documents which detail aspects of her life, the court proceedings or her time in gaol. The book is well-researched with a myriad of details about daily life of the time which feel authentic and natural.

Louisa’s voice is unsophisticated, humble and meek, as we would imagine for a woman of her station, someone who could not vote or own land or a business independently of her husband. And yet there is something powerful about her voice, something compelling about the way she tells us her story first-hand, as she relates the difficulties and hardships of her life, not in such a way as to garner sympathy, but simply presenting the facts as they stand. Of course, Louisa is long dead and who is to know what she really thought and felt, but Lee has done a thoughtful and considered job of imagining how it might have occurred. And we are kept guessing until the very end of the book as to whether Louisa will confess to the crimes in her last days, or whether she will die still protesting her innocence. Either way, Louisa Collins comes to life in this book – her personality and appearance and her relationships with others have been richly invoked – and by the end of the story, we feel we have come to know intimate details about her, and have witnessed one possible perspective of what might have happened and how and why certain events might have taken place.