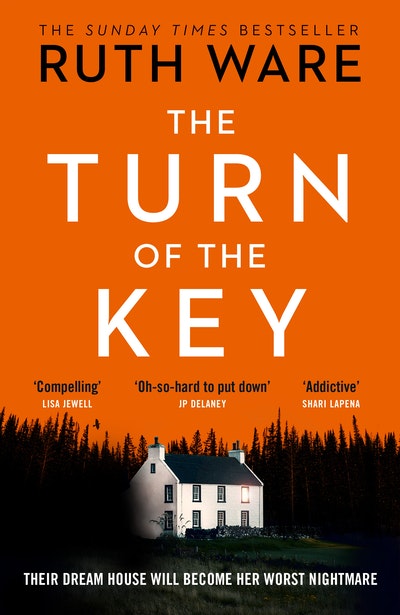

Great psychological thrillers have the reader second-guessing themselves at every turn, wondering whether or not the novel has a reliable narrator, choosing which characters to align with, deciding who is villain and who is victim. Ruth Ware executes this extremely well in The Turn of the Key (Penguin Random House 2019), an unsettling and creepy story of a nanny, Rowan, who accepts a position in the isolated place of Heatherbrae House in the Scottish Highlands.

Two important facts to know about Heatherbrae: first, it used to have a different name, and has quite the reputation throughout the local villages as being haunted, or the setting for some chilling crimes. Second, it has been bought and renovated to within an inch of its life by a couple of edgy architects, who have the whole house wired on a ‘smart system’, so that when you talk to it, it talks back, everything is controlled by an app, and there are security cameras (almost) everywhere. So the house as setting is already disturbing enough, and then we learn that Rowan is the fifth nanny in only a short time, the others fleeing in fear (of what, we don’t yet know).

As soon as Rowan arrives at her post, to care for young girls Maddie and Ellie, and baby Petra (and the temporarily absent adolescent Rhiannon), the parents Sandra and Bill go away for work, leaving her with the children, the occasional appearance of the rather odd housekeeper, Jean, and the groundsman/driver, Jack, who lives in an apartment above the stables.

The book begins in a very interesting and promising way – Rowan has been convicted of murdering a child and is trying to write a letter to someone whom she hopes might be able to help her and assert her innocence. Her first few tries are abandoned, but then she begins her letter, which then becomes her speaking to this person and telling them her story. I found this a little implausible – that she would write a novel-length letter. But soon enough we forget it is told to us second-hand, as we are immersed in the story. The author – or rather Rowan – reminds us though, intermittently throughout the narrative, which brings us with a thump back to her current predicament of being incarcerated.

Ware is like a double agent; her novel a spider web of confusion. During the first third to half of the book, I was sure I knew what was going on. It even felt somewhat predictable: of course I knew whether the narrator was reliable or not, of course I knew the list of possible perpetrators. But then the narrative slid from my grip and I began to understand that I didn’t really know anything.

The creepy, disturbing, menacing factor is dialled right up as the book progresses, with genuinely frightening scenes that had my heart racing. The tension increases and I felt I had lost whatever control I thought I had of the reins of this horse; events were unpredictable and unexpected. During the final quarter of the book, Ware really comes into her own, pulling off twist after twist, and shock after shock, that are completely surprising. The novel finishes with three letters / emails that were such a jolt, I had to reread them to make sure I had understood what had happened.