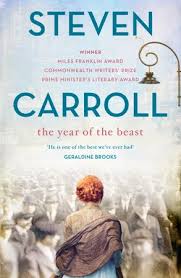

The Year of the Beast (Harper Collins 2019) is the concluding episode of author Steven Carroll’s epic Glenroy series; the series as a whole covers the decades from 1917 to 1977, and The Year of the Beast – although published last – is actually the beginning of the story. Set in Melbourne in 1917 during the year of the referendum for conscription, the beast of the title is a kind of grasping, wild, tumultuous, rabid, uncontrollable madness that has the city – and in fact, the whole country – in its grip. Soldiers are dying, white feathers are being left on the doorsteps of those who are not fighting, the church is trying valiantly to keep hold of its moral authority, women are beginning to rise up to have their voices heard. Change is in the air.

At the centre of the story is 40-year-old Maryanne, seven months pregnant and unmarried. Those who have read the other Glenroy books in the series will know Maryanne as an historical figure, an ancestor, from a photo or from family stories. But in this book, her own story is revealed. The past and the present are nicely balanced by the occasional reference by Carroll to characters such as Michael and Vic, Maryanne’s descendants who feature in other books in the series. The image of a gleaming jet plane crossing the sky is completely out of place in Maryanne’s 1917 world, and yet prescient for the life that will come for those who outlive her.

The central issue of the story is that Maryanne must face the wrath of the church, which wants her to give up her unborn child into the care of the nuns and therefore cleanse the child’s soul from sin (although Maryanne herself will remain stained), or to choose to bring the child up herself, with only her sister Katherine, for support. This book captures the societal norms of the time, reflected by the situation of one woman struggling against the odds.

The Year of the Beast is very introspective, providing a constant stream-of-consciousness dialogue from Maryanne about her own intimate life, her circumstances, the cultural mood of the time, and the push and pull of those in power and those who confront and challenge them. But while the novel does capture this period of history, I found many of Maryanne’s actions, and her general demeanour, at times implausible and difficult to believe. The phrase ‘the male gaze’ kept running through my mind as I was reading; I couldn’t quite put my finger on why, but something about this heavily pregnant woman didn’t ring true for me. This is only the second Glenroy book I have read out of six; perhaps with the benefit of reading the others my opinion would change or soften. In any event, Steven Carroll is one of Australia’s well-known authors, and his work does provide a compelling narrative of the individual against the crowd and the passing of legacies from one generation to the next, and it places in perspective the passage of time and the transience of one human life when set against the backdrop of history.