A clever short story writer uses each story to immerse readers into a microcosm of a world until we are thoroughly engaged and our hooks have begun to curl into the characters and the setting and the plot, and then as suddenly they wrench us out again, into the open air, where we lie gasping for breath and wondering what just happened. This is exactly what Laura Elvery does again and again in her debut collection of stories, Trick of the Light (UQP 2018). While we are still recovering from one, brushing the story droplets from our skin, she immerses us in another, in a completely different time and place; she introduces us to people that are as real and whole and fully formed as in the previous story; she makes us believe that now we are here, in this new place, that this is real and the rest was imagined. And then she does it again. And again.

Over and over, with 24 stories, she plunges us into realities that shock with a cold sting. Each story is a skilfully contained vignette, a glimpse into the intricacies of someone else’s life, a direct emotional connection. I am still thinking about the girl with the rosy cheeks who applies radioactive paint to watches; the stranger who showed up at the cabin. The poetic language of A Man About a Moon resonates still. I feel I know Kit and Kayla and Sarah and Marlee. These stories are weighed down by the past or occasionally – as in Dots and Spaces – buoyed up by the future. They speak of love and longing, of despair and distance, of frustration and thwarted ambition. In Brushed Bright Bones, reincarnation seems not only possible, but inevitable, and we wonder why we haven’t noticed earlier. There is the strangeness of For What We Are About To Receive, the childhood reminiscences of What You Really Collect Is Always Yourself, the fear – and anxiety about ageing – in Acrobat. We meet a sinister teacher and a struggling mother. We feel a young man’s acute sense of loss in the wake of a friend’s suicide; the sharp interruption of violence into childhood; the urgent desperation of a refugee.

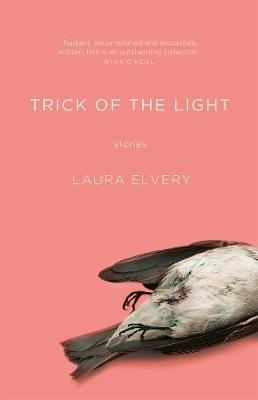

The endings of these stories are never tidy or neat; the endings appear more as a pause in the tale, a temporary cessation. We expect them to start up again at any moment. We imagine them continuing on, even without us as witness. Like all good stories, they leave us wanting more. Like the dead bird on the cover, they hint at what might have been, and at what is no longer; at life cut short and freedom curtailed.

What joins these stories together is keen emotional insight, and an attention to detail that brings every character into clear focus. The stories are poignant, distressing, sad, funny, hopeful and searching. They remind us of the many permutations of human behaviour. The myriad cross-sections of people’s lives are rendered through the careful choice of a phrase or a sentence that sings with meaning. This feels less like a collection by the one author, and more like a collected volume of stories by different authors, each accomplished in their own way.

And if each story is an immersion, the collection is a series of rock pools, linked by the thinnest of threads. In each one lies the cleansing water of change and renewal. From each one we rise, the words streaming from our bodies in great sheets of silver, shining and slick.